The Tethered Beads of Time: The photograph pinned to the wallboard in the upper left hand corner is of my mother’s recently born great-grandchild, Mira. She is the second daughter of the oldest son, Matthew, of my brother, Jim, and his wife, Mercedes. Linda and I attended the wedding of Matthew and his spouse, Heather, in Las Vegas.

August 4, 2019

On Friday night, July 12, 2019, my mother was sent to St. Mary’s hospital in Long Beach because of very high blood pressure and low levels of oxygen absorption. She had been losing weight in the preceding weeks, and was down to 115 pounds. She spent four full days at the hospital, during which I had a chance to talk with Dr. Ferrera, a superb physician who had attended my mother the only previous time she had stayed there for any length of time. In the fall of 1996, she was hospitalized for pneumonia, but fought it off rather quickly and her health then leveled off for the next 20 months.

Dr. Ferrara was refreshingly honest, in his assessment of my mother’s condition three years after his first remediation. He assured me that her vital sign were fundamentally sound. “She’s not in the check-out line, or if she is, she’s way back.”

At that time, I decided not to shift my mother to hospice care. Tonight, though, August 4, 2019, having been informed that her breathing is being assisted with an oxygen delivery system, it appears that it is time for her to “enter hospice,” not that I have a lot of faith in that process. A poet friend once told me that hospice was just another word for slowly starving a person to death, and that that was exactly what she had watched her mother endure; unfortunately, nothing she tried to do could alleviate the suffering that hospice only exacerbated.

The alternative, of course, is to have her shuttled back and forth from the SNF to the hospital.

James Tate once used as an epigraph for a poem a sentence from Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men: “You are alone with the Alone, and it is his move.”

Apparently, tonight, it is my move, though the first clause is in full effect.

This evening, as I said goodbye to her, I promised that I would return tomorrow. “I look forward to it,” she said, and I can only hope that she will remember that expectation, when she wakes during the night, bewildered as she seems to be as to what is happening to her.

Sylvia Mohr and Bill Mohr — First Week of June, 2019

I wrote the following blog entry in the early summer of 2019, but never posted it.

Sunday, June 9, 2019

The past week was extraordinarily difficult and discouraging. My mother is now 97 and a half years old, and if attaining the distinction of now being among the “very old” has been an ordeal for her, she has not been without some minimal companionship. Out of her half-dozen children, I am the one chosen to have been her intercessor. I am most certainly not her favorite child, but that is how the deck of cards worked out. No one else lives within a hundred miles of her, and for the past three years, I am the only one who has seen her week after week, month after month.

It should be noted that my mother’s health (both mental and physical) was on the verge of collapse in November, 2016, and that without the unflagging assistance of my brother, Jim, in San Diego, my mother most likely would not have been able to stabilize and recover; nor would my mother have ended up in the Long Beach area, where I could address her distress, unless my sister, Joni, who lives in Israel, had intervened in the summer of 2016 to extract her from a self-inflicted plight. But it’s been largely a solitary endeavor, made all the more difficult because I do not feel any particular love for my mother. (Post-script to that comment: In some weirdly distant parallel way to how mothers teach themselves to “love” the strange creature that has arrived from within themselves, I have found myself able to feel compassion for her that is as close to a love for her that I will ever have.)

She has not always lived in Long Beach, California. My mother lived, in fact, for over a half-century in the southwestern most pocket of San Diego, a neighborhood that was once part of Imperial Beach, but was annexed by San Diego a couple of decades ago. I left that area in the mid-1960s because it was a catastrophic psychic landscape. In caring for my mother, I confront the embodiment of a childhood environment in which I was treated with contempt and disdain, bullied to a degree that still leaves me stultified with self-loathing. Of course it could have been worse. I could have been a child in Iraq, or Yemen, or forced to bear arms at the age of nine in some equatorial civil war. Instead, I was merely a poor, ugly, and physically weak youth who managed to endure what seemed to be an intolerable amount of abuse without engaging in some hideous retaliation. I told myself that I would do something when I got — though I had no idea what it was — that would have greater dignity to it than my tormentors could ever believe. Whether I have done that or not remains unknown. In any case, each morning I take a deep breath, and steady my will, reciting as I often do Yeats’s translation of Oedipus at Colonus, as a morning prayer.

This past Friday, I found myself at the welfare office in Compton, hoping that the Medi-Cal paperwork to renew my mother’s assistance could somehow be expedited. Compton was not my destination of choice; but I had received no communications whatsoever from the Department of Public Social Service in Los Angeles County for over a year, and my guess was that my mother’s caseworker was located in Compton because it was the office closest to the one where I had filed her original application, when she was living near the northernmost border of Orange County. My guess was spot on.

It was a long morning. “If you hadn’t been called in a half-hour, you should have let someone know,” one worker told me, after I had waited for an hour. Needless to say, no one told me when I checked in how long it would be reasonable to wait before inquiring about the process. I did not want to seem demanding or presumptuous about some degree of entitlement, and so I sat and waited, and sat and waited before expressing my curiosity about the expected length of wait.

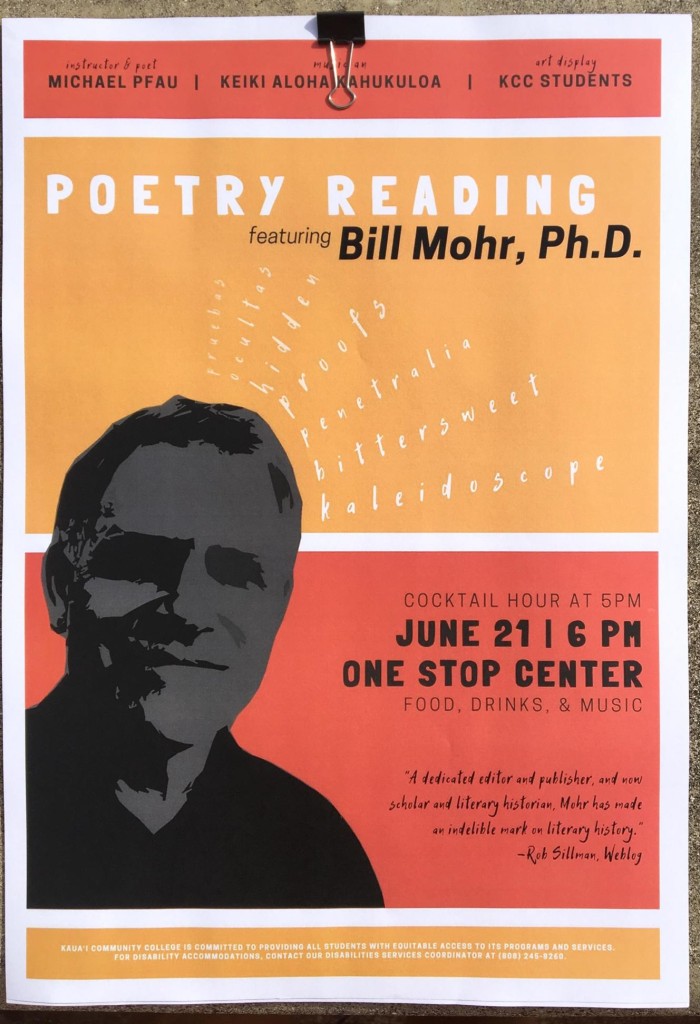

I mention all this merely to dilute any jealousy than some readers might feel in taking note of the above poster. One might think, “Wow, Bit Mohr is going to Hawaii to read his poetry.” Well, yes, I am pleased — very pleased — to be asked to read my poems there; and I look forward to it.

But I am exceptionally weary. The ordeal of being my mother’s caretaker the past three years has combined with other disproportionate assignments in other areas of my professional life to leave me skeptical about my ability to enjoy this respite of a journey. Perhaps it will seem to others that I am enjoying it. I, too, wear a mask.

(As a postscript: It is a tribute to the kindness of Nicole and Erik, my hosts in Hawaii, that I was able to take considerable comfort and pleasure from this trip. Thank you both, again and again.)

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr