January 1, 2016 — Top Ten Picks of David Ulin; The Monolingualism of American Literature

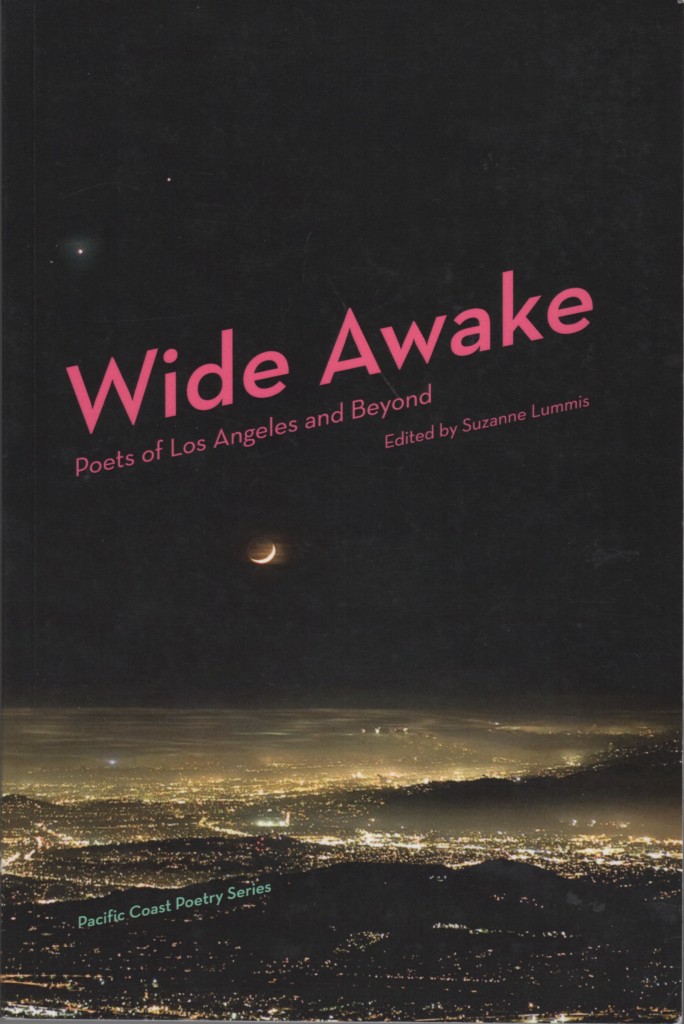

LA Times Book Critic David Ulin has edited several anthologies himself, a fact that deserves underlining when he includes Suzanne Lummis’s Wide Awake: Poets of Los Angeles and Beyond as one of his ten favorite books published in 2015. One doesn’t have to have edited an anthology of poets to gauge the value of such an effort, but it certainly tends to make one a more judicious reader of anthologies. Lummis, too, is a veteran of this kind of editorial project; she co-edited an earlier anthology with almost the same subtitle back in the early 1990s. The high marks that Ulin gives Lummis’s latest anthology are much appreciated in the Los Angeles poetry community, if only because L.A. poets have not always had a smooth ride in the L.A. Times. In particular, one can recollect that Robert Kirsch once anointed my first anthology, The Streets Inside: Ten Los Angeles Poets (Momentum Press, 1978) as an indication of a “golden age” of Los Angeles poetry. Unfortunately, not everybody who worked at the LA Times Book Review agreed with Kirsch’s assessment, and poets were regarded as cultural orphans of their own success. I’ll put it simply: it’s nice to be appreciated again. Ulin implicitly suggests the exponential growth of the diverse scenes here by pointing out that Wide Awake is “magnificent” both in quantity (it contains “the work of more than 100 poets”) and quality (it “reveal(s) the depths and power of the city’s poetic sensibility”). That David Ulin appreciates the efforts of the diverse communities of poets in this city enough to award Lummis’s anthology a top ten pick is very gratifying, and I hope Suzanne Lummis is savoring the acknowledgement.

The last paragraph in Carolyn Kellogg’s end-of-the-year commentary in the LA Times is also worth further consideration. In referring to the choice of a Russian writer for the Nobel Prize in Literature this year, Kellogg cites an article that appeared back in 2008 in which a member of the Nobel selection committee commented that American writing is “too insular.” The charge is true, I’m afraid, though the full quotation I’ve been able to dig up is even more revealing:

“The U.S. is too isolated, too insular. They don’t translate enough and don’t really participate in the big dialogue of literature,” (Horace) Engdahl said. “That ignorance is restraining.”

The real gripe that the Swedish academy has with American writing lies in the evidence of its insularity: “They don’t translate enough.” This could be translated, so to speak, as “You don’t care about us; so why should we care about you?” Fair enough, and it brought to mind how I recently found that my most widely distributed posting in this blog for the entire year of 2015 was “Against the Monolingual Torture of Writers,” which was originally posted back in early September. For some reason, it took off in December, and had over 300 pageviews, with 161 human visits, of which 149 were new visitors to my blog. My post was firmly on the side of the Swedish academy, and perhaps it caught the attention of someone in Europe who was surprised to find an American writer at odds with his peers.

Fortunately for me, my blog is not dependent on American book publishers for advertising in order to keep itself going. If it were, I could see retribution heading my way lickety-split. Believe me, I’ve seen it happen. The announcement earlier today of the death of Natalie Cole recoiled with references to “Unforgettable,” a song that her father had made famous and which the daughter reprised by having a version in which her voice was blended in a duet with his. Back when the father-daughter version was soaring up the charts, the newspaper I was working at as a typesetter started running cartoons with a slightly satirical edge to them about the music industry. The publisher must have thought it would make his paper “different” from the other trade papers. What he didn’t count on was that you can only get away with making fun of something that everybody shares a dislike of (i.e., politicians). The music industry takes itself very seriously, and when the front page ran a cartoon of Natalie Cole saying to a skeleton figure of her father, “Hey, Dad, you’re stepping on my lines,” (or something similarly sarcastic), the music label that released Cole’s remake let my paper know that it wasn’t just cancelling advertising of that particular song in the next issue or the issue after: all advertising by that label was forthwith cancelled. Or at least that’s the version that I heard in the hallway. I do remember some rather tense editorial and salespeople faces walking past me for a week or so until the crisis was resolved. The first thing to go, of course, was the contract with the cartoonist, nor was a replacement sought.

So, yes, once again, it would make American literature more interesting if the writers here asked themselves at some point if what they are writing would at all interest someone who can only read Spanish or Chinese. Are you saying something profound enough or insightfully witty enough to merit the travail required to translate it? I do appreciate how hard it is to attain that level of writing. My first book of poems in another language has only been published after over 40 years of writing. Surely, though, those poets who have won so many more awards that I have during that time have some explanation for why their work does not seem to make a transition beyond the wall of American monolingualism.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr