I have heard myself referred to as a “local” poet, a phrase that almost implicitly is meant to diminish the status of any artist or poet. Of course, I am hardly the only one besmirched with that term. I remember giving a talk at the Getty Research Institute in the fall of 1996 about the poets of Venice West and being challenged about the value of their insularity. “Who wants to be local?” Michael Roth asked me in front of a roomful of professors who were known for their scholarship on the city of Los Angeles.

At the time, I didn’t have an answer that adequately provided an escape hatch from my seeming intellectual provinciality. The point of the year-long seminar I was part of for a few months was to examine Los Angeles as a primary instance of what Peter Schjeldahl called a “transmission city,” a status long accorded New York, Paris, and London. The culture industry, with its global capacity to replicate hypnotic cinematic images, made readers of literary magazines with circulations of less a thousand people seem utterly irrelevant. That poets wanted to generate a gift exchange economy in direct opposition to the corporate seizure of cultural capital was regarded as too confined to be a serious strategy. Such an evaluation had consequences: a person sitting by herself, and reading a book published by Red Hill Press or Bombshelter Press or Momentum Press or Little Caesar Press or rare avis press or Mudborn Press was not endowed with any sliver of literary enfranchisement; in the 1970s, and yet… (yes, let’s pause here…) and yet it was poetry published by dozens of “local” small presses around the country that largely set in motion the multiculturalism that eventually aroused demands known as DEI. The fact that the backlash has been so ferocious in the past decade only shows that the “local” efforts of small presses and independent arts organizations (including Beyond Baroque, the Woman’s Building; the World Stage; and Tia Chucha) have been more than coterie efforts. Their antagonism toward centralized control of culture has earned its place as a form of pragmatic resistance.

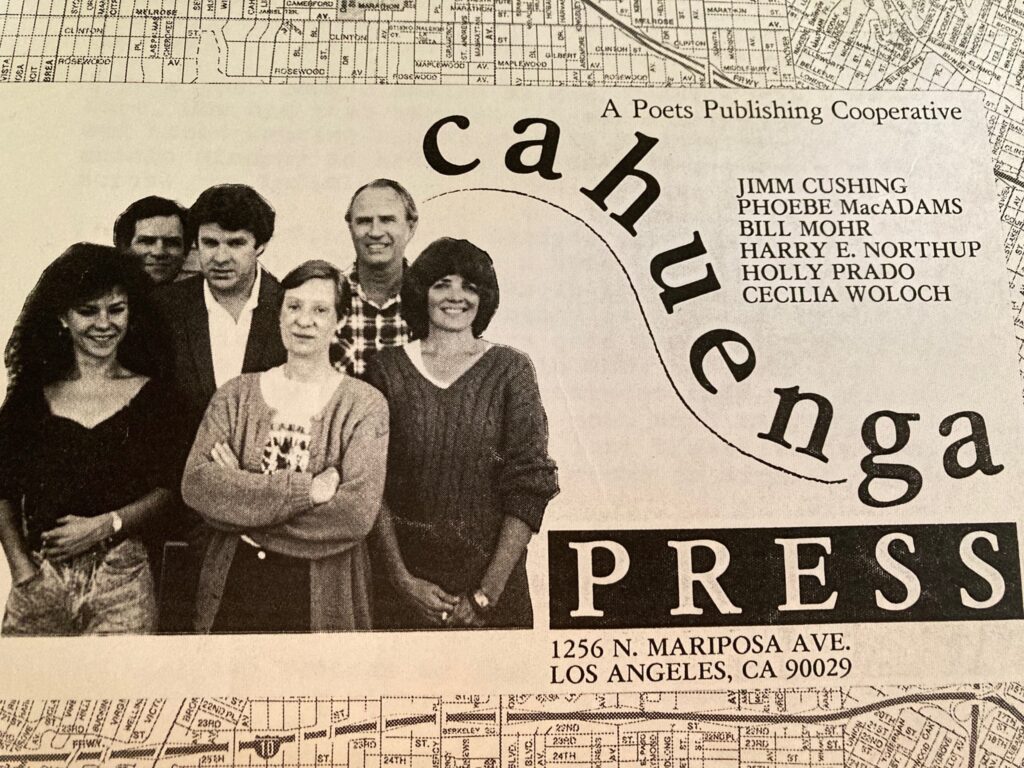

In particular, I would like today to point to an example of a publishing project launched by Harry Northup and Holly Prado that is still at work: Cahuenga Press. While subsequent collectives, such as What Books, have emerged and made an enormous contribution to a vivacious literary ecosystem imbued with nektonic energy, Cahuenga has distinguished itself with a series of volumes that directly confront the issue of being “local.”

Here is an early flyer. As briefly as I was a working contributor to this project, it remains one of the efforts I am most proud to have helped get underway.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr