Sunday, April 28, 2024

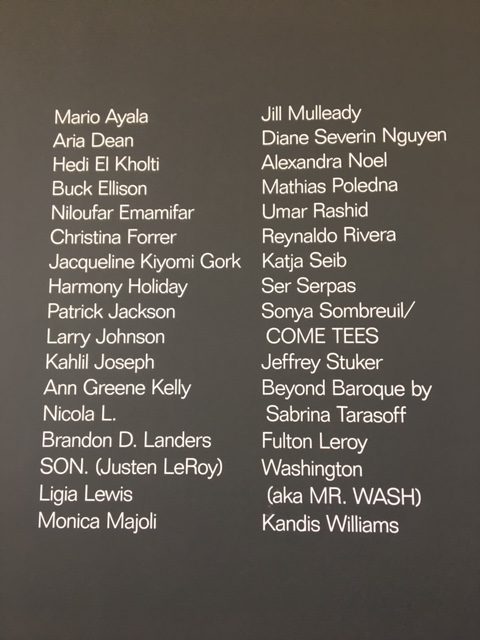

“FORM AND FORMLESS” at the Shatto Gallery (April 20 – May 18, 2024)

https://www.shattogallery.com/?utm_campaign=345a1c1e-5344-4da6-bdb2-34f7749ab9b8&utm_source=so&utm_medium=mail&cid=0252bf6a-2a83-4c02-b545-78430028324a

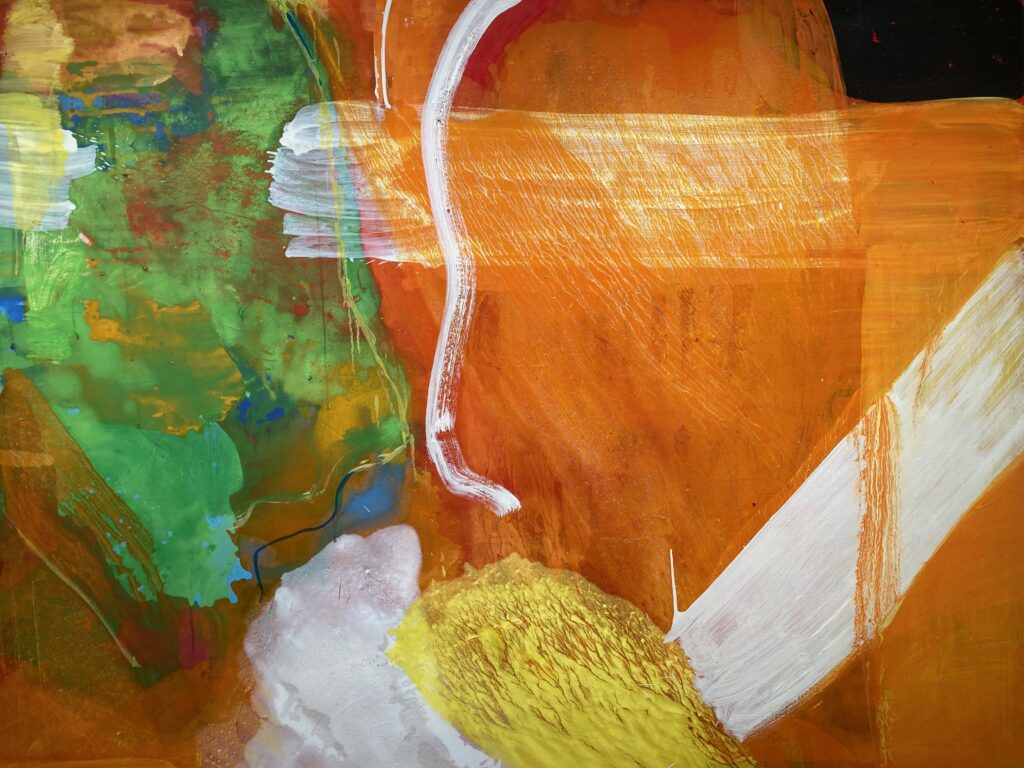

“You and Me” (2023)

The Hammer Museum currently has an exhibition featuring the work of Korean artists who contributed to the Conceptual art movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Only two of the contributing artists to the Hammer’s retrospective are women, and while this gender disparity probably reflects the actual social and artistic hierarchy of that period and movement in South Korea, it nevertheless leaves one wishing that the counterbalance had more public visibility. Perhaps, though, comprehensiveness is simply an unstable paradox, and any attempt to provide retrospective knowledge about overlooked scenes in postmodern art ends up obscuring those who unrelentingly pursue extensions of a traditional practice. Along with the current show at the Torrance Art Museum, “Risky Business,” Hyesook Park’s show at the Shatto Gallery in Koreatown in Los Angeles, “Form and Formless,” affirms the persistent viability of painting as the ever-renewing core of visual art. If Park has committed herself to painting for over 45 years, her durability derives from a meditative vision which, above all else, involves the restoration of trust as the essential ingredient of the social imagination. As one views and absorbs an artist’s paintings, the physical object of the painting itself replenishes the pleasures of human curiosity about another’s inner, intimate life, no matter how austere or agitated. Yet another bond coheres, however, in that process of giving one’s attention to a painting. Describing that bond is almost impossible: a phrase such as liminal reciprocity hardly suffices. All I know is that it involves vulnerability, which leads us back to trust. Only with that mutual commitment can the forms of color in a painting enable us to recalibrate our daily lives. This exhibition earns one’s trust by the ease of how the conversation between the painting and the viewer can get more complicated than anticipated.

Most of Park’s paintings at the Shatto Gallery are from the past half-dozen years. Fortunately, the layout of the show takes care not to impose too easy a chronological connection between each of the paintings, even if a pair of my favorite ones share the same title. The first painting entitled “You and Me” (30″ x 36″, 2023), on the back wall of the front desk, is emblematic of the jouissance that permeates the ecstatic union depicted in the larger, older version of 2018, in an adjacent room. One is grateful to have them separated, however, because it allows other paintings to provide the context for the reconciling fusion of two people. “Landing” (2024), for instance, depicts an equine eruption with a pure frontal force. Rarely has “death-in-life” been caught with such a ravishing buffer: surely the frothy cream of violet tinging the rims of the entrance/exit of bestial sentience can have no other purpose than to be a benign restoration. In that mode, a nearby work, “Ladies in Light” (2024″), reminds me of the empowering radiance in the late Lee Mullican’s work.

“Ladies in Light”

Of the paintings that one returns to after a first walk around, however, the most captivating is “Dear Father III” (2020), in which the unsaddled rear of a black horse, in profile, with a single leg demarcating a vertical horizon line, glows with an equipoise of the unseen vistas once inhabited by the creature’s vigor. The descent toward the hoof has both the unrelenting solidity that emanates from animal flesh and the mythic power that extrudes into the paradigmatic binary of the centaur. If the horse’s rear is unsaddled, it is because the unseen fromt of the horse is the rider as the insurgent, sentient beast, the patriarch as the always imagined, yet ultimately elusive progenitor. Nearby that painting is another of the exhibition’s largest embodiments of symbolic congruity between humans and other animals. “An Odd Melancholy of Being Alive,” depicts a bird gazing across a vast field of migration to the cone-shaped nest of its destiny, in which a white oval in the diagonal corner waits for a black lever to fling its futurity into the bittersweetness of an individual journey.

“Dear Father III”

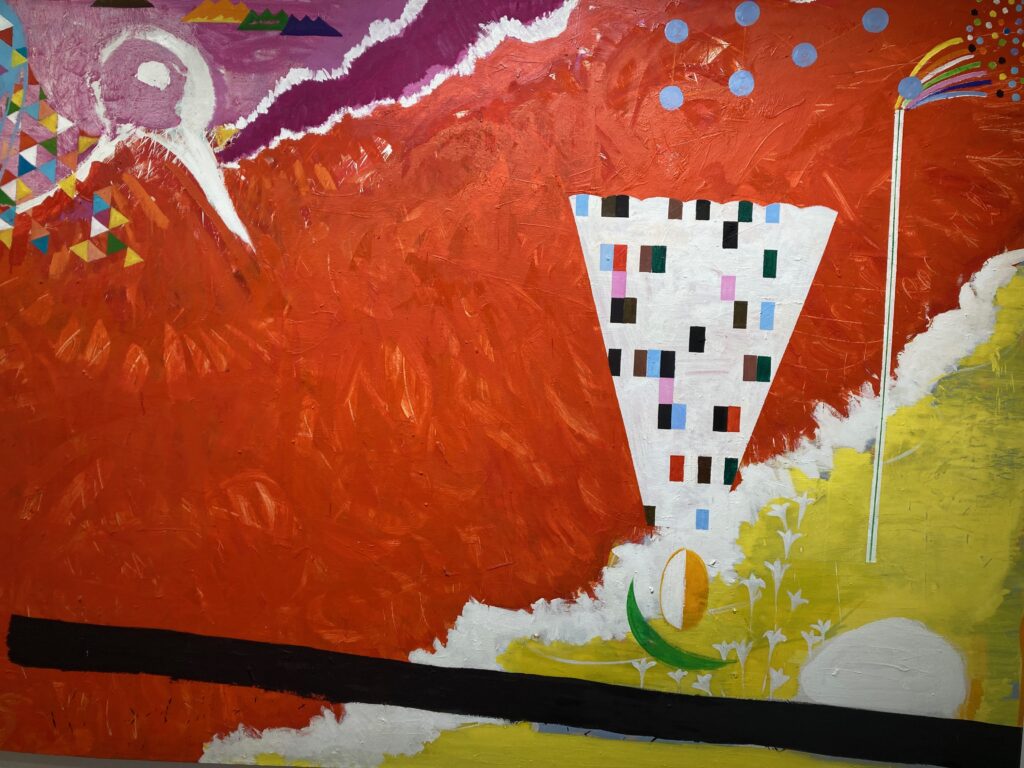

“Santa Monica” exudes a sensorium akin to a jubilant, fully-embodied watercolor: the sun on the horizon is not the piercing “yellow” one might associate its usual decision with, but the intense red of the utterly molten fusion that is closer to its “true” color, if one were to record an image of the sun’s vitality as registered during the recent eclipse at earth sky.org. Instead, it is the palm tree and its frond that radiate the intensity described by Wallace Stevens in “The Palm at the End of the Mind.” Several paintings are aligned with “Santa Monica,” including “Windy Day” and “Watermelon,” which palpitate with the joy of being alive, as opposed to its “odd melancholy.”

“An Odd Melancholy of Being Alive”

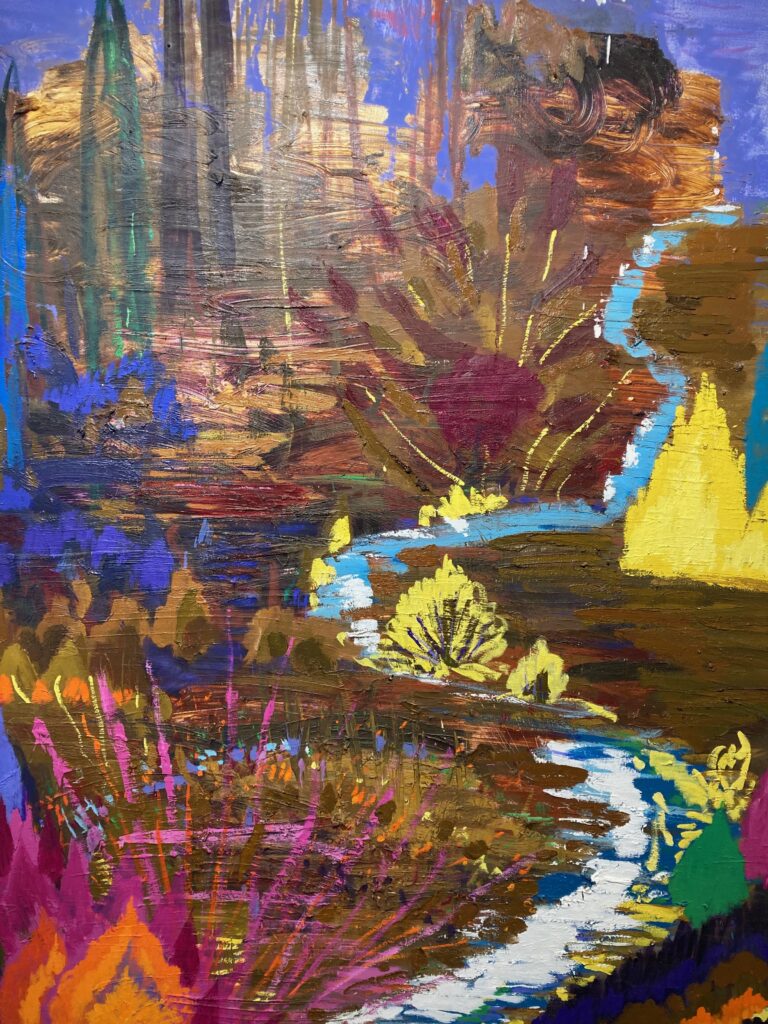

Finally, one would be to remiss to visit this exhibition and not set aside enough time to find one’s inner point of equilibrium as one gazes at “Unknown Destiny.” This painting reminds me of a poem I wrote several years ago called “The Headwaters of Nirvana,” for it conjures up a hard-won levitation, as if the fecund gorgeousness of sensual perception could encompass the entire, constant redoubling of a journey along the lines of Matsuo Basho’s “Narrow Road to the Deep North.” Given that Park paints at the studio that is in the dry, barren foothills east of San Bernardino, one learns from this painting how one can draw upon memories of a pilgrimage to reinforce the resolve of the present moment and remain centered in one’s florescence.

(“Unknown Destiny”

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr