This is a translation into Spanish of an article I wrote several years ago that was published in a special issue of Luvina magazine devoted to Southern California writing.

I also wish, at this moment, to once again thank the editors of BONOBOS EDITORES for publishing a bilingual collection of my poems, PRUEBAS OCULTAS, with translations by Jose Luis Rico and Robin Myers, in 2015, and for all the visits I made to Mexico to read my poems.

***

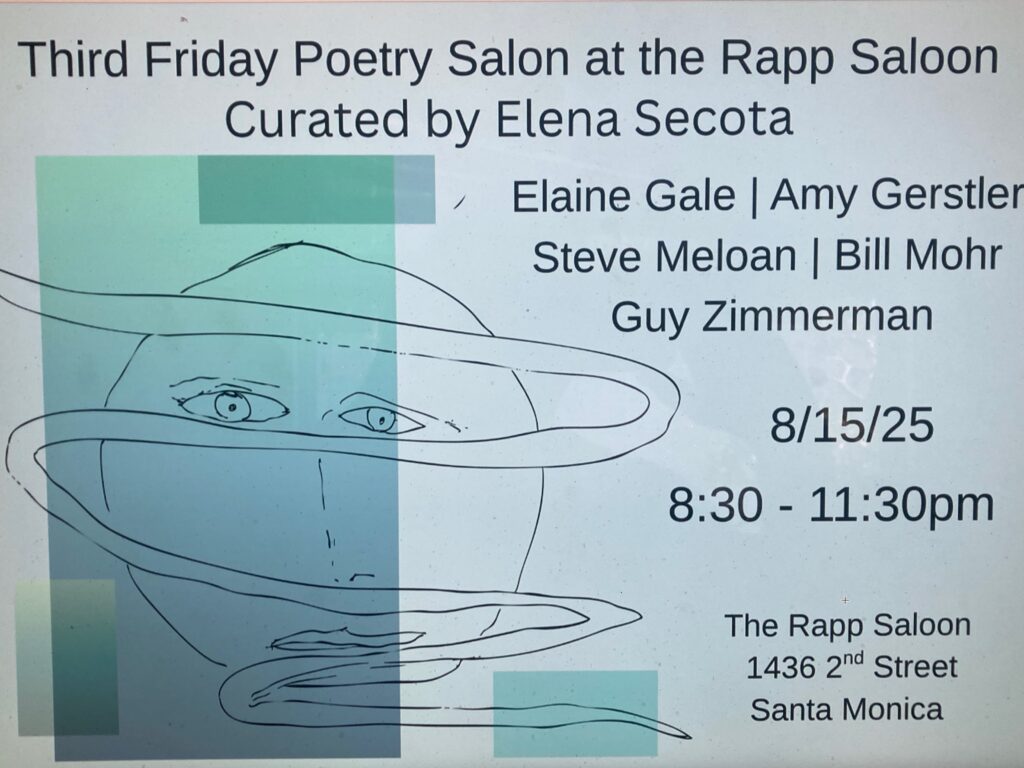

Escenas y movimientos en la poesía del sur de California / Bill Mohr

Con demasiada frecuencia las críticas de poesía norteamericana privilegian a San Francisco, Berkeley y Oakland, superponiendo lugares que evocan los más memorables sucesos y movimientos de la poesía de la Costa Oeste, como el Renacimiento de Berkley, la escena beat de San Francisco y, más recientemente, el lenguaje/escritura. Sin embargo, también se aplica a Los Ángeles el ímpetu foráneo detrás del señalamiento de William Everson de que los cánones de la Costa Oeste valoran la creatividad y el juicio canónico de la Costa Este, si bien es más difícil trazar una cartografía de la energía fractal del escenario poético de la ciudad. Aunque los sondeos de ficción funcionan probablemente mejor si se enfocan en autores individuales, el desarrollo de la poesía norteamericana, casi todo el medio siglo pasado, está íntimamente ligado a comunidades de escritores y editores. La viabilidad de la red de talleres, lecturas públicas, revistas e imprentas en Los Ángeles durante los años setenta y ochenta dependió del acceso a instalaciones de producción como New Comp Graphis en Beyonde Baroque, en la ciudad costera de Venice, para ayudar a los poetas a demarcar sus comunidades de manera orgánica y autorreflexiva.

Al abrazar con gran fervor la tendencia antinómica en la poesía norteamericana originalmente formulada por Roy Harvey Pearce, estas comunidades y círculos intersectados produjeron una poesía que por mucho superaba en cantidad y calidad la escritura producida sobre Los Ángeles en forma de poemas ocasionales por residentes temporales o por quienes vivían a una pasmosa distancia. Por ello este sondeo se enfocará en los escenarios y comunidades que han florecido y se han entremezclado en L.A. a partir de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Este énfasis no pretende desestimar la notable, aunque breve, presencia de poetas como W.B. Yeats, Hart Crane o James Dickey, ni borrar de la historia de la región los años jóvenes de Robinson Jeffers, puesto que casi todos los escritos que formarán el patrimonio poético de L.A. han surgido durante este período más reciente.

Las revistas underground y la escena del jazz en Venice West,

1948-1968

Durante todo el período que estamos considerando, los poetas de L.A., Long Beach y ciudades aledañas generalmente lanzaban sus revistas sin apoyo institucional y sin los dóciles recursos de los capitales literarios y culturales. Para mediados de 1950, L.A. cobijó un rango impresionante de revistas literarias, entre las más importantes Trace de James Boyer May. Trace apareció en 1951 como directorio de pequeñas revistas y subsistió hasta alcanzar casi seis docenas de ediciones. Su lista de contribuyentes incluyó a muchos poetas como William Pillin, Bert Meyers y Alvaro Cardona-Hine, quien apareció en el California Quarterly, fundado por el poeta de la lista negra Tom McGrath en 1951, o Coastlines, lanzada por sus protegidos Gene Frumkin y Mel Weisburd a mediados de la década de los cincuenta y que permaneció hasta 1964. El California Quarterly dedicó sus páginas no sólo a los poetas subversivos de L.A., como Don Gordon y Edwin Rofle, sino también a quienes trataban de evadir la censura oficial del período macarthista. La cacería de brujas logró impedir la distribución de la película clásica sobre la clase trabajadora, Salt of the Earth(Sal de la tierra), pero el California Quarterly tomó represalias dedicándole toda una edición del verano de 1953 al guión de Michael Wilson.

En 1958, los editores de Coastlines presentaron una lectura de Allen Ginsberg en una casa de L.A. que utilizaban como sede. Durante dicha presentación, Ginsberg se desnudó completamente para hacerle el favor a un alborotador demostrándole lo que quería decir con «desnudez» (estar en cueros), término usado para un poema despojado de todo ornamento literario. Uno de los jóvenes poetas asistentes, Stuart Perkoff, ya había fundado una comunidad de poetas beat en la comunidad costera de Venice, descrita por su antiguo mentor, Lawrence Lipton, como «la barriada junto al mar». Fuera de enclaves residenciales y cafés, Venice West alcanzó la suficiente prominencia para ser citada por Donald Allen en su Introducción a La nueva poesía americana. Perkoff y Bruce Boyd, parte de ese núcleo, fueron incluidos en esa antología, junto a Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Denise Levertov, Charles Olson y Robert Duncan. Aunque con el tiempo el poemario Voices of the Lady: Collected Poems (Voces de la Dama: poemas recogidos) fue publicado por la National Poetry Foundation en 1997, la mayoría de los poetas beat de L.A., como John Thomas, William Margolis y Charlie Foster, permanecen inexcusablemente fuera de todos los estudios de literatura beat. Sin embargo, este apareamiento de lecturas de poesía con música de jazz fue un precursor de la poesía oral de L.A. y de su parentesco con la música punk.

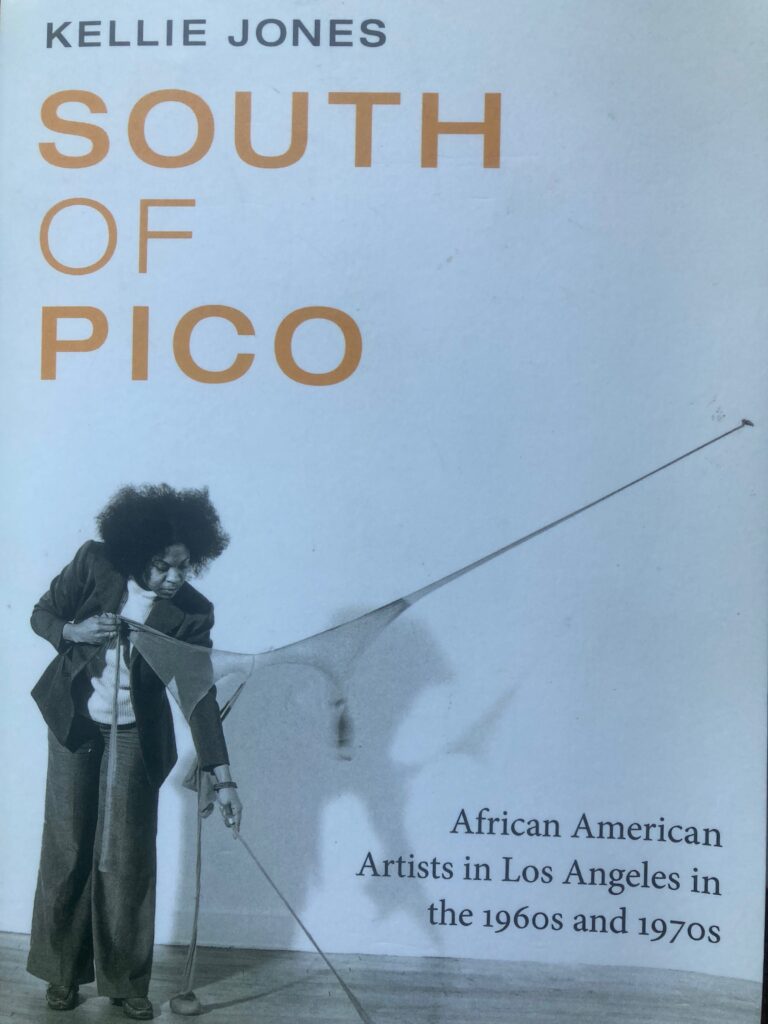

Para principios de los sesenta, las aspiraciones de Venice West, basadas en un programa idealista de pobreza voluntaria, habían sucumbido al encanto devastador de la drogadicción. Sin embargo, otras comunidades de L.A., cuya pobreza era involuntaria, finalmente se rebelaron. Después del levantamiento de Watts en 1965, las instituciones de la Costa Este trataron de ejercer su largueza esperando sofocar las tendencias militares en las comunidades afroamericanas para impedir cualquier posicionamiento de los Black Panthers y otras organizaciones radicales. Las fundaciones Ford y Rockefeller reforzaron las contribuciones de personajes famosos de Hollywood como Gregory Peck y Budd Shulberg para desarrollar el Taller Watts Writers en el Centro Cultural del Barrio Urbano que publicó poesía en su propia revista, Neworld. Aunque el Taller Watts Writers produjo trabajos de muchos géneros, incluyendo teatro, el legado poético de dicha empresa sigue siendo su logro más significativo. Varios de los poetas que de allí surgieron siguen escribiendo hoy, incluyendo a Eric Priestley, K. Curtis Lyle, Ka’mau Da’oud, Otis O’Solomon, y Quincy Troupe.

Beyond Baroque y el renacimiento de Venice (1968-1985)

Venice no permaneció inactiva por mucho tiempo. En 1968, Drury Smith, antiguo profesor de inglés de preparatoria, compró un edificio abandonado sobre el bulevar West Washington y empezó a publicar una nueva revista literaria, Beyond Baroque. Cuando el dinero de las suscripciones no se materializó, Smith abrió una imprenta y abrió sus puertas a la comunidad de Venice. A los pocos meses, el escritor de novelas policiacas Joseph Hansen, junto con un amigo poeta, John Harris, abrieron un taller de poesía gratuito todos los miércoles por la noche. Sigue siendo el taller gratuito de mayor duración ofrecido por cualquier organización significativa de artes literarias alternativas en todo Estados Unidos. Beyond Baroque también siguió editando una revista bajo diferentes títulos incluyendo NeWLetterS, New y Obras. Sufrió variantes de producción, como el cambio a formato de papel de prensa, que se distribuyó gratuitamente. En 1972 un editor, James Krusoe, empezó una serie de lecturas los viernes por la noche. Dentro de los primeros dos años, la muchedumbre se agolpaba hasta la acera y se instaló un sistema de sonido exterior para transmitir la interpretación. Para cuando Dennis Cooper, editor de la revista Little Caesar, y su vástago, una pequeña imprenta, asumieron la serie de lecturas a finales de 1979, Beyond Baroque ya no era un asunto de colectas. Inspirado en la rebeldía e ingenio de la música punk, Cooper combinó su interés por la escuela de poetas de Nueva York y el lenguaje/escritura con una firme lealtad hacia prometedores poetas locales como David Trinidad y Amy Gerstler, quienes eventualmente ganaron el National Book Critics Circle Award. Simultáneamente con la inauguración de Cooper, Beyond Baroque transfirió la biblioteca de su pequeña imprenta y su equipo de composición tipográfica de New Comp Graphics, de su limitado espacio al complejo de dos pisos del viejo Venice City Hall. Bajo la dirección artística de Cooper la organización surgió como un centro de poesía de reconocimiento nacional. La pequeña biblioteca de la imprenta, fundada por la antigua editora de Coastlines, Alexandra Garrett, aumentó su acervo a 10 mil libros y grabaciones. El New Comp Graphics Center proporcionó el respaldo tecnológico que los jóvenes poetas aspirantes y los editores necesitaban para lanzar libros y revistas. Con la partida de Cooper hacia la ciudad de Nueva York, Beyond Baroque apenas logró sobrevivir. El muy necesitado subsidio del National Endowment for the Arts no se materializó y la institución casi cerró sus puertas. La banda punk X, cuyos compositores fundadores Exene Cervenka y John Doe se reunían en el taller de poesía Beyond Baroque, ofreció un concierto y recaudaron más de 10 mil dólares, lo suficiente para mantener sus puertas abiertas. Al paso de los años ha habido suficientes personas generosas que han contribuido para mantener Beyond Baroque bajo una serie de directores artísticos que incluye a Manazar Gamboa, Jocelyn Fisher, Dennis Phillips, D. B. Finnegan, Tosh Berman y, desde mediados de los noventa, Fred Dewey. Durante más o menos una década la programación artística empezó a favorecer la escritura de ficción, pero bajo el resuelto liderazgo de Dewey, desde mediados de los noventa el enfoque regresó a la poesía. En diciembre de 2008, al concluir la celebración de su cuadragésimo aniversario, Beyond Baroque renovó el arrendamiento del Old City Hall

en Venice por otros 25 años, apalancando así potencialmente la escena de Venice bastante más allá de la vida de los miembros fundadores del taller de las noches de miércoles.

Página y tablado: palabra de pie y hablada

Casi simultáneamente al desarrollo de Beyond Baroque, «Los Ángeles… discretamente surgió como un importante centro de poesía de la Costa Oriente, donde una forma de performance de poesía populista, llamado de diferentes formas —“Poesía de Pie”, “Poesía Fácil” o “Poesía de Long Beach”—, combina la comedia y la poesía post-beat ejemplificada por Charles Bukowski». El poeta de Long Beach y profesor Gerald

Locklin unió fuerzas con Ron Koertge, profesor del Pasadena City College, para formar el núcleo de este movimiento, frecuentemente mal comprendido hasta por quienes lo admiran. Otros miembros del núcleo son Laurel Ann Bogen, Elliot Fried, Ray Zepeda, Austin Straus, Jack Grapes, Eloise Klein Healy, Suzanne Lummis y Edward Field, cuyo primer libro, merecedor del Premio de Poesía Lamont, Stand Up, Friend, With Me (Ponte de pie, amigo, conmigo, 1964), le dio nombre al grupo. En un ensayo introductorio a la tercera edición de la antología Stand Up Poetry (2002), Webb advierte que la poesía stand up «se agrupa a veces con la poesía “de calle” de tendencia antiliteraria… o se le confunde con el performance». Ambas agrupaciones, afirma, «son un error». Un buen poema stand up (de pie) exige tanto arte literario como cualquier otro poema… La poesía stand up se escribe para la página impresa, teniendo presente que la poesía siempre ha sido un arte oral y que alcanza su culminación cuando se lee en voz alta». Webb señala diez aspectos que siempre están presentes en un poema stand up, y que el humor, la posibilidad de actuarlo y la claridad son las principales cualidades hasta en un poema de tema lúgubre, como el de Suzanne Lumiss, «Letter to my Assailant» («Carta a mi asaltante»). Sin embargo, con mayor frecuencia los poemas stand up utilizan temas de la cultura popular y de material no poético, como el linóleo o una caja de crayolas, por ejemplo en el poema «Coloring» («Colorear»), de Koertge: «¿Quién escuchó jamás el Premio Nobel / de Colorear? ¿Quién dice “Éste es mi hijo. / Tiene un doctorado en Colorear?”».

Por su éxito y continua popularidad, los poetas stand up son los poetas de L.A. más fácilmente accesibles, tanto en sentido literal como por la facilidad de obtener sus libros. Las primeras dos ediciones de la antología de Stand Up Poetry, publicadas por Charles Harper Webb, están agotadas desde hace mucho tiempo, pero la tercera edición ofrece no sólo una muestra representativa de la obra producida por los poetas más conocidos de L.A., sino un medio para comparar y contrastar su obra con poetas norteamericanos como James Tate, Tom Lux y Denise Duhamel, cuya obra ocasionalmente se traslapa con stand up.

Un descendiente de la escuela stand up es la palabra hablada contingente que se desarrolló en L.A., en gran medida a través de los esfuerzos de un antiguo productor de música pop, Harve Robert Kubernik. Sus primeras empresas fueron antologías en vinilo, pero para principios de los noventa su nómina de casetes y discos compactos para solo bajo la etiqueta de New Alliance incluía a los poetas Holly Prado, Harry Northup, Michael C. Ford, Linda Albertano, Steve Abee y Michael Lally. Poetas como Cervenka, Doe y Dave Alvin, conocidos primordialmente como músicos punk, y Henry Rollins —quien suplementó su voluminosa autopublicación en la imprenta 2.13.61 con libros de poetas neo-beat como Ellyn Maybe— se alinearon bajo el movimiento de la palabra hablada, que con frecuencia salía al aire en el programa «El hombre en la Luna», de Liza Richardson, en la estación de radio kcrw. Es probable que muchos de estos poetas leyeran en la tienda de guitarras McCabe en Santa Mónica, en la tienda de discos Bebop de San Fernando Valley o en una librería o biblioteca. El miembro más destacado de estas comunidades poéticas populares es Wanda Coleman, oriunda de Watts. «Soy víctima de un mal agüero por partida cuádruple», afirmó Coleman, desafiante, en una ocasión. «Soy mujer negra y poeta nacida en L.A.». Sin embargo, Coleman empezó a publicar su poesía en las pequeñas revistas de L.A. Hasta la fecha ha publicado una docena de libros de poesía y prosa en la editorial Black Sparrow de Santa Rosa y con frecuencia ha grabado material con Kubernik. Otras poetas como Kate Braverman y Laura Ann Bogen, envalentonadas por la habilidad de Coleman de entremezclar la poética del performance con la acústica cáustica de la prosodia callejera, empezaron también a fundir página y escenario. Tanto Coleman como Bogen aparecen en las tres antologías de poesía de pie editadas por Webb, quien se mudó a L.A. después de una exitosa carrera como rockero en la zona noroeste del Pacífico.

Escenas de librería y la rebelde vanguardia

Esencial para la supervivencia de todas estas escenas y comunidades fue el hecho de que, para finales de los años setenta, L.A. ya contaba con un grupo de librerías independientes dispuestas a surtir una y otra vez libros de poesía y revistas, incluyendo un nidal favorito de poesía de pie, Pearl, editado por tres mujeres poetas de Long Beach (Joan Jobe Smith, Barbara Hauk y Marilyn Johnson), y Third Rail (Tercer riel), por Doren Robbins y Uri Hertz. Clave para este desarrollo fue la tienda Papa Beach, situada al oeste de L.A., conocida desde un principio por su voluntad de proveer literatura marxista y ofrecer consultas sobre la leva militar en el desván trasero. Esta tienda lanzó su propia revista literaria con un apodo en diminutivo como título: Bachy, que circuló de 1972 hasta 1980. Lee Hickman fue su editor poético en 1977, para después establecer Temblor, revista que antes de llegar a su décima edición alcanzó reputación nacional cuando Hickman dejó su cargo al enfermar de sida. El enfoque principal de Hickman en Temblor eran los poetas que formaban parte de una vanguardia rebelde. Compartió este interés con Paul Vangelisti, poeta y editor que se había mudado de San Francisco, su ciudad natal, a L.A., hacia finales de los sesenta. Considerándose a sí mismo un artista exiliado, Vangelisti editó Invisible City durante los años setenta, publicó alrededor de dos docenas de volúmenes de la poesía vitalmente experimental a través de su sello, la imprenta Red Hill, además de ser un gran traductor de poesía italiana y editar una serie de revistas literarias, incluyendo New Review of Literature y Or. Aunque los primeros seis números de Invisible City se centraron en poetas como Bukowski, los colaboradores que más emblematizaban el libre acercamiento (la actitud bohemia) de Vangelisti y de su editor asociado, John McBride, fueron Amiri Baraka y Jack Hirschman. Este último tradujo a Antonin Artaud, René Depestre y Vladimir Maiakovsky. Hirschman se mudó a San Francisco a mediados de los setenta, pero regresó con frecuencia a Los Ángeles a hacer lecturas.

Hacia mediados de los ochenta, la mayoría de las librerías independientes más importantes habían cerrado o apenas sobrevivían. Un editor que se las arregló para seguir adelante a pesar de la merma de espacios fue Douglas Messerli, poeta editor que llegó a L.A. a mediados de los ochtenta y convirtió su sello Sun & Moonen una de las editoriales más eclécticas de poesía vanguardista de Estados Unidos. Su antología más voluminosa, From the Other Side of the Century (Del otro lado de la centuria, 1994), apenas registró la presencia de poetas de su hogar adoptivo. Sin embargo, la antología Innovative Poetry (Poesía inovadora) de Messerli entremezcla experimentalistas dispares de L.A. con neosurrealistas como Will Alexander, Dennis Phillips y poetas del lenguaje como Diane Ward, quien se había asentado en L.A. Messerli había demostrado su apoyo a poetas que experimentaban con poemas largos, en serie. Si Messerli operaba libre de cualquier restricción impuesta por las instituciones patrocinadoras, otros editores de L.A. con credenciales vanguardistas equivalentes corrieron con menor suerte. Con traducciones centelleantes de César Vallejo y una vigorosa red de poetas experimentales creada en torno a su primera revista de poesía, Caterpillar, Clayton Eshleman se había establecido como provocador cultural por su habilidad para encontrar poetas que pudieran desafiar la ortodoxia de la poesía americana antes de vivir esporádicamente en L.A. La segunda revista de Eshleman, Sulfur, empezó a publicarse gracias a la generosidad de la Universidad CalTech, donde enseñaba Eshleman, quien en poco tiempo se topó con problemas de censura, y una vez más su determinación visionaria le permitió sostener su publicación continua. Eshleman no se interesaba mucho en los poetas que consideraba parte de la escena local, pero su revista lucía una dirección de Pasadena. Por mucho que Eshleman desdeñara la región, logró escribir un número considerable de poemas en residencia y establecer en esa arboleda de científicos de cohetes la idea de que el arte de la poesía es el reto más sobrecogedor que se pueda presentar ante la imaginación humana.

La poesía feminista, la poesía multicultural y de la academia

Muchas mujeres se alinearon en torno a las artes visuales y la comunidad teatral del Edificio de la Mujer (The Woman’s Building), que floreció en L.A. como institución feminista durante casi dos décadas. Cobijada en lo que fuera en otra época una escuela de artes antes de mudarse a la sección industrial del centro de L.A., el Edificio de la Mujer incluyó eventualmente una imprenta que entrenaba a mujeres para componer y operar una máquina tipográfica. Su revista, Chrysalis, no era una revista literaria como tal sino un espacio para el comentario cultural feminista, incluyendo la escritura creativa de poetas como Eloise Klein Healy y Deena Metzger. El evento literario de mayor importancia que tuvo lugar en el Edificio de la Mujer fue la conferencia de mujeres escritoras en 1975, registrada en Feasts (Fiestas, 1976), un libro experimental de prosa poética mucho más audaz y memorable que otros textos contemporáneos como My Life (Mi vida, 1987) de Lyn Hejinian. Mientras que Healy, Metzger y Prado siguen afiliadas al movimiento de la pequeña editorial de la Costa Oeste, otros poetas asociados a la serie de lecturas en el Edificio de la Mujer o al Centro Gráfico de la Mujer in situ exploraron el seductor archipiélago del «exilio cultural» que Paul Vangelisti ha atribuido a una «extrema presencia y ausencia», compendiada en la aposición de Igor Stravinsky, «espléndido aislamiento». Desire in L.A. (Deseo en L.A.) de Martha Ronk, quien ha enseñado literatura renacentista en el Occidental College por muchos años, es un excelente ejemplo de esta identidad provisional:

Las olas se vuelven para salir al mar,

una ciudad entera se dilata como el universo,

cada uno conduce cañones hacia arriba, cada viento centrífugo llegando

más allá de lo que antaño fueran los límites de una ciudad

y nadie de nosotros puede dejar

de empujar más allá de nuestro tiempo, nuestro dinero, la necesidad

de algunas afueras de una ciudad ya totalmente en las afueras,

buscando alcanzar, como el deseo erótico, las partes más profundas.

Dedos y cuellos amanerados se alargan más allá de sí mismos,

duele la piel secándose al viento,

esperando encontrar una expansión transparente

hacia los elevados alcances de la ni siquiera creencia,

pero ansiando nuestro propio descreimiento

y esa imagen de otra falda

levantada por el aire cálido, ligeramente sucio de una rejilla abierta.

Para otros poetas, el exilio es más literal. Bertolt Brecht pudo regresar a Alemania después de pasar más de una década en Santa Mónica. Aleida Rodríguez, nacida en Cuba, tituló su primera colección de poemas Garden of Exile (Jardín del exilio) como declaración de un destino ineluctable. En «My Mother’s Art» («El arte de mi madre») examina las consecuencias del destierro y se enfoca en la manera en que el exilio impacta la transformación social de cada generación. El poema de Rodríguez revela el diálogo feminista de autoempoderamiento que tuvo lugar en el Edificio de la Mujer, cosechando proyectos como la editorial Paradiseasí como la editorial Birds of a Feather de la propia Rodríguez y la revista rara avis:

En mi sueño, mi madre se sentaba en el piso,

haciendo varias pinturas pequeñas de Los Ángeles.

Reconocí el ayuntamiento, asomándose como una gigante pluma Rapidográfica

detrás de algunos edificios bajos amarillos

que el sol quemaba ferozmente.

Y el Hotel Ambassador,

su largo toldo y marchitado glamour,

una tarde azulada filtrándose en su descolorida fachada.

Las pinturas yacían en el piso, a su alrededor

y claramente ella estaba llena de goce.

…

¿Cómo nunca supe esto?

¿Que mi madre era una gran artista?

¿Y que lo hacía con tanta naturalidad,

de manera tan informal, sentada simplemente en el piso,

su trabajo, evidente producto de su disfrute,

en todo su derredor?

Casi todos los poetas que he mencionado después del esbozo de Venice West y del Taller Watts Writers, aparecieron en una u otra de las dos antología que edité, The Streets Inside (Las calles de adentro, 1978) y Poetry Loves Poetry(La poesía ama la poesía, 1985), en las que aparecen más de cinco docenas de poetas. Michelle T. Clinton, una poeta afroamericana que, como Coleman, había asistido a los talleres semanales de Beyond Baroque, y Suzanne Lummis, quien a finales de los años setenta se había mudado del programa de maestría de la Universidad de Cal State en Fresno a L.A., ambas incluidas en mi segunda antología, pasaron durante la siguiente década a trabajar como antologistas. La antología de Clinton, Invocation L.A.: Urban Multicultural Poetry (Invocación L.A.: Poesía multicultural urbana, 1989), coeditada por Sesshu Foster y Naomi Quinonez, se enfoca en la comunidad rápidamente creciente de poetas del Tercer Mundo en L.A., incluyendo a Manazar Gamboa, Gloria Álvarez, Rubén Martínez, Russell Leong, Víctor Valle, Amy Uyematsu y Lyyn Manning, pero también incluye a poetas angloamericanos como Karen Holden y Fred Voss. La antología de Suzanne Lummis Grand Passion (Gran pasión, 1995), que incluye poemas de festivales de poesía de la ciudad, incorpora un amplio registro de poetas de etnicidad identificable con conciencia de su propia etnia. En años recientes, poetas como Marisela Norte, Ramón García, Max Benavídez y el difunto Gil Cuadros han colaborado en muchas otras comunidades.

Las universidades y departamentos resguardados en varios suburbios de California del Sur posibilitan que poetas con inclinación académica se ganen la vida como profesores al mismo tiempo que se reconcilian con el clima cultural de L.A. Si los profesores-poetas se quedaron inicialmente absortos frente al aparente fervor provinciano, también descubrieron eventualmente el aspecto providencial de las contradicciones regionales. El aparente antiintelectualismo de los poetas performance escondía un profundo respeto hacia cualquier poeta dispuesto a reconocer las ventajas de que la tradición y la experimentación compartan los mismos anaqueles. A principios de los setenta solamente un puñado de poetas académicos como Ann Stanford, Jascha Kessler, Charles Gullans y Henri Coulette parecían trabajar en la ciudad. Para la última década del siglo xx y la primera del xxi se podría reunir una tentadora antología compuesta únicamente de poetas con ese tipo de afiliación: Gail Wronsky, Tim Steele, Ralph Angel, David St. John, Steven Yenser, Sarah Maclay, Cecilia Woloch, Harryette Mullen, B. H. Fairchild, Christopher Buckley, Dorothy Barressi, el difunto Dick Barnes, Robert Mezey, Molly Bendall, Patty Seyburn, Robert Peters y James McMichael.

Mientras que los lectores de otras ciudades en primera instancia pudieran no identificar a estos poetas con L.A., casi todos ellos escriben poemas en los que calles específicas de L.A. permean las imágenes y los temas. Sencillamente es casi imposible imaginar a David St. John escribiendo un poema como The Face: A Novella in Verse (La cara: una novela en verso, 2004) excepto como consecuencia directa de años de trabajo en L.A. Efectivamente, tal vez uno de los aspectos más sorprendentes de la poesía en L.A. no sea simplemente su elasticidad y resistencia, sino que los poetas tienen un interés por los poemas largos, ya sea el inacabado pero magistral «Tiresias» o Blue Guide (Guía azul, 2006) de Steven Yenser, u Odalisque (Odalisca, 2007) de Mark Salerno. El libro de meditación sobre la ciudad de Pasadena de James McMichael, Four Good Things (Cuatro cosas buenas, 1980), fue un primer modelo para muchos de estos proyectos.

Al volver la mirada sobre las diversas comunidades de poetas que han habitado cañones, callejuelas, bulevares y playas de L.A., uno se pregunta cómo es posible que tal diversidad pudiera adaptarse a una congestión literaria semejante a sus famosas autopistas. En mi introducción a Poetry Loves Poetry (La poesía ama la poesía), sugerí que uno de los elementos que atrajeron a los poetas a L.A., y que sigue sosteniéndolos, es lo mismo que trajo aquí a la industria fílmica: la calidad de la luz, que posee mayor variedad de intensidad y tonalidades que ningún otro lugar de Estados Unidos. La mayoría de los poetas que siguen trabajando en esta ciudad encuentran su fuerza no sólo en la luz, sino en la abierta aceptación de la visibilidad de cada comunidad hacia los otros y en la cristalización que les espera después de su paciente labor.

Traducción de Verónica Grossi

FROM: Luvina, issue number 57

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr