Wednesday, December 27, 2017

ENDLESS SONG RETURNING: Selecting the “Selected Poems of Larry Eigner”

In the second half of the 1970s, several poets I talked to mentioned at some point how the Selected Poems of Frank O’Hara (first published in 1974) did not include many of the poems they had grown fond of through their extended reading of O’Hara’s Collected Poems, which had appeared three years before the condensed version. When I conducted an interview by mail with Donald Allen, I deliberately kept away from any question that might have irked him, and yet I wish he had been willing to talk, in the mid-1990s, on record about his editing of O’Hara. He was notoriously reluctant to answer autobiographical questions, however, and I felt fortunate to get any substantial information from him about his childhood and youth. There has been a subsequent Selected Poems of O’Hara, though I don’t expect to have spent much time with it until I get around to writing an essay on FOH.

I suspect that sometime in the mid-2040s there will be another “Selected Poems of Larry Eigner,” whose four-volume set of Collected Poems will provide much to choose from. I was recently given an early Christmas present by my esteemed colleague at CSULB, George Hart, in the form of a copy of Calligraphy / Typewriters: The Selected Poems of Larry Eigner. Geroge knew of my interest in Eigner’s work because I hauled back, from some academic conference at the start of this decade, all four volumes that Stanford University Press had published, at a considerable discount, I am happy to report. Professor Hart has been working on a project involving Eigner’s letters, some of which have been published in Poetry magazine, and at one point I volunteered to let him borrow my set of Eigner’s volumes so that he could refer to it in his school office and keep his own personal copy to work with at home.

Calligraphy / Typewriters will no doubt be the primary source for Eigner’s poems for the rest of this decade and all of the next one, and it certainly accomplishes one of its major purposes: to make more of Eigner’s poems part of the postmodern canon that is taught in colleges and universities. (Less and less poetry is taught at the high school level, and it is highly unlikely that Eigner’s poems will be read by anyone but a very precocious epebe at the second level.) For those who first became acquainted with Eigner’s poetry through Donald Allen’s classic anthology, it might come as a slight surprise to realize that the first poem by Eigner in that volume, “A Fete” (dated by Allen as written in July, 1951) is not included by Curtis Faville and Robert Grenier in the Selected. Nor are three other poems favored by Allen included in Eigner’s Selected: “A Gone”; “Passages”; and “Keep Me Still for I Do Not Want to Dream.” In a similar pruning, Allen’s sequel to NAP, The Postmoderns, included nine poems by Eigner, at least three of which are not in calligraphy typewriters.

I don’t have the time right now to do what is the most obvious piece of research: what other anthologized poems by Eigner are not included in this Selected? This is not necessarily meant to be a criticism of Faville and Grenier’s editorial choices. If anything, it is meant to call attention to the considerable challenge they faced in assembling this collection for the University of Alabama Press. It is, in fact, the mark of a major poet that no one can agree on a list of their best poems or be amicable about which ones serve as most representative of the poet’s major themes. I am always dismayed at how many of my favorite poems by Emily Dickinson are not included in anthology selections.

If I were to draw upon this collection as a source for an anthology of postmodern poetry, and limit myself only to this volume, here is a list of the poems that would make my short list of Larry Eigner’s representative work:

“a poem is a” – page 123 (September 4, 1967)

“p o e t r y” (for Jane Creighton) – page 235 (November 26, 1974)

“the reality behind” – page 183 (June 23, 1971)

“how it works” – page 188 (July 26, 1971)

“shadowy / gesticulations” – page 189 (August 30, 1971)

“space space space space” – pages 306-307 (February 5-13, 1986)

“the snow / bank / melts” – page 120 (March 14-24, 1967)

“head full / of birds the languages / of the world” – page 121 (March 30 – April 23, 1967)

“the flock / on the ground” – page 241 (9/12/75)

“the street / plastered with leaves” – page 132 (November 3, 1967)

“many how a” (for Clark Coolidge) – page 232 (July 2, 1974)

w i n t e r – page 196 (December 23, 1971)

“finishing” – page 212 (October 24, 1972)

“a full life” – page 195 (December 19-21, 1971)

“far” – page 233 (October 10, 1974)

“the / frosted car” – page 245 (12/24/75)

“hills” – page 261 (September 24, 1978)

“earth slopes and” – page 264 (March 7, 1979)

“anything” – page 200 (March 24, 1972)

“morning / again” – page 321 (June 4, 1991)

The poem dated September 24, 1978 is the initial one in the “Berkeley” section of calligraphy typewriters. I remember first seeing that poem in Ron Silliman’s blog, on September 18, 2007. Silliman described the poem as consisting of “five nouns” and insisted that the poem “can’t really be read any other way.” I remain skeptical of that claim, since my first internal embodiment and registration of that poem was to hear “clouds” as a verb. The shift and merge of noun and verb in that poem is precisely the “readiness” called in the title of the book in which that poem was first collected. As a parallel demonstration of blending, the same emphatic nominative repetition occurs in the middle of the poem “the reality behind,” in which a poetics that intertwines subject and predicate reveals an image worth depending on.

Anyone intrigued by Eigner’s poetry would be well advised to scour anthologies of the past half-century to see what other poems have been nominated as worthy of repeated readings. Most certainly the ones chosen by Allen deserve to be set alongside those in Calligraphy / Typewriters, and I hope that an expanded version of this volume includes Allen’s choices. For that matter, so does a compressed version of this volume need Allen’s choices, too.

All this aside, however, it cannot be emphasized enough what a fine job Curtis Faville and Robert Grenier have done in conveying the incremental wisdom to be found Eigner’s poems through a successive arrangement faithful to his development as a poet. Grenier, who is one of least appreciated and most intriguing poets in the United States, and Faville have made their task look easy. I would like to add that it was gratifying to see a continuity in the contributors to this project. The late Leslie Scalapino’s O Books Fund supported this book’s wherewithal, and George Mattingly, the legendary publisher of Blue Wind books, chipped in with cover design. My congratulations to both of them for an outstanding job.

Charles Bernstein, one of the Modern and Contemporary Poetry series editors at the University of Alabama Press (along with Hank Lazar), makes an astute decision to write a concise introduction. My only quibble with that self-imposed limitation is that he doesn’t remind the reader sufficiently of Eigner’s debt to Williams. The use of “again,” for instance, as a pivotal enfolding most probably derives its impetus in Eigner’s poetry from the end of Williams’s reductive version of his own poem:

come

white

sweet

May

again

And while all of the poets named by Bernstein are indeed part of the conversation to/from/in which Eigner scoured his faceted diction, so too we find other unexpected voices enlarging Eigner’s context, for Eigner indeed was a poet with “a mind of winter,” wo most certainly saw the nothing that was is there, and the nothing that is. Once again, however, I would not want my own idiosyncratic engagement with this book to distract readers from what truly deserves our applause. The paragraph by Bernstein that flows from page x to page xi, the one that begins “Eigner’s work offers,” is an absolutely brilliant piece of insightful recognition.

Finally, I would note that the blurbs on the first inside page are all by men. Is there no other woman poet-critic other than Lyn Hejinian who is willing to speak up for Eigner’s poetry? In asking this question, I am not so much referring to commentary before the book’s publication, but serious writing about it in the decade to come. If a young female critic wants to become the next Marjorie Perloff, a chapter-length article on Eigner would be a good place to start.

(Note on Eigner’s poems in The New American Poetry: Of his nine poems, perhaps it is just a coincidence that both the first one and the last one feature automobile imagery in their opening lines: “Now they have two cars to clean” is the opening line of “Do It Yrself”; and “A Fete” begins “The children were frightened by crescendos / cars coming forward in the movies.” On the other hand, perhaps Allen was (unconsciously?) responding to Eigner’s physical limitations and embellishing his “image” of mobility’s kinship by invoking a car culture that was certainly a major trope for many of the poets featured in this anthology.)

POEMS SELECTED FOR THE FOLLOWING PAIR OF ANTHOLOGIES

The New American Poetry

A Fete

Noise grimaced

B

Environ s

O p e n

A Gone

Passages

Keep me still, for I do not want to dream

Do it yrself

THE POSTMODERNS

“from the sustaining air” (February, 1953; SP 8)

Do it yrself

“the dark swimmers” (July, 1954; CT: Selected Poems, 10)

“the wind like an ocean” (“the wind an ocean”; August, 1965; CT: Selected Poems, 101)

Letter for Duncan (August 31, 1959; CT: Selected Poems, 35)

“flake diamond of / the sea” (May 14,1960; CT: Selected Poems, 59)

“That the neighborhood might be covered”

“I have felt it as they’ve said” (September,1954; CT: Selected Poems, 54)

“don’t go”

“the bare tree / alternate”

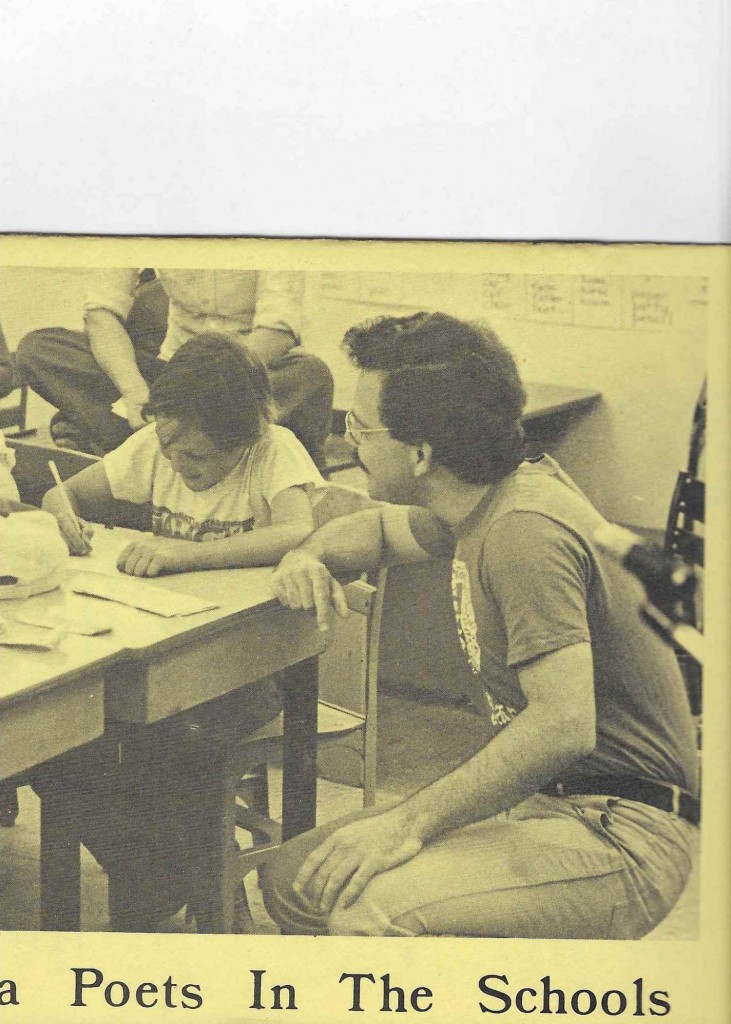

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr