I have twice visited the Hammer Museum in the past month, both times shortly after a visit to the best dentist in the world, Dr. William Chin. I owe the good fortune of having a dentist worth a 30 mile drive through Los Angeles freeway traffic to the recommendation I got in the 1980s from my dear friends, Bob and Judy Chinello. So much of life is the odd chance meeting. My recollection is that I met Bob and Judy through Sandi Tanhouser, who had known them through her own job. One day in Ocean Park she went to vote and told me when she returned from the polls that she had bumped into friends who turned out to be living just down the street. Over the years, both Bob and Judy were among the handful (along with Brooks and Lea Ann Roddan) who encouraged me when things often looked bleakest, especially in the 1990s. I suppose it’s hard not to get sentimental in one’s old age, but I remember visiting Bob and Judy when they had moved to the San Fernando Valley and going out to the front yard to rake leaves and how it was one of the happiest moments of my life.

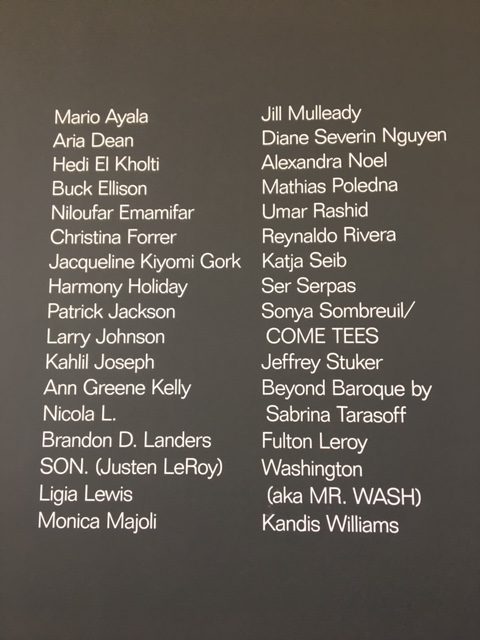

The first time I went to the “Made in L.A. 2020 (a version)” show I expected to see the installation created by Sabrina Tarasoff, but it turned out that her work is only at the Huntington Library. There is, however, a plaque on a wall at the top of a staircase that provides information about her project. The museum was more crowded than I expected it to be and there was a line to see one of the exhibits that was long enough to make me want to get on the road back to Long Beach before afternoon traffic got too dense.

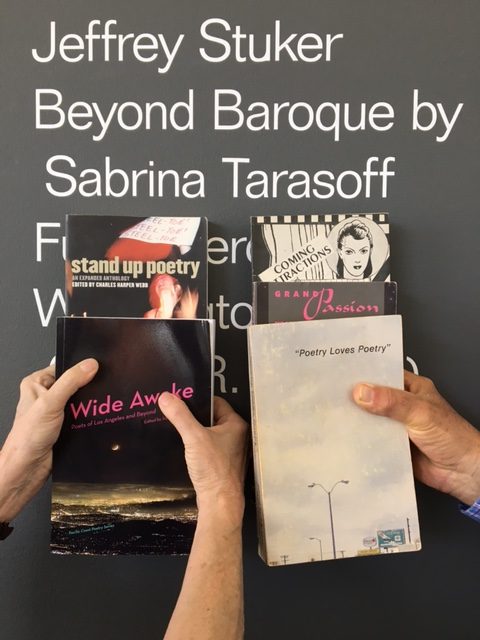

The second time I went to the Hammer was this past week. This time it was Linda who had the dental appointment, and we dropped by the apartment of our long-time friend Laurel Ann Bogen, on the way to the Hammer and picked her up, too. On my first visit it had occurred to me to return with copies of several anthologies of Los Angeles poets that could help “frame” Tarasoff’s project. Linda took photographs of Laurel and me holding up anthologies along the plaque listing the Beyond Baroque project.

I was grateful that attendance was much lower the second time so that we could enjoy Brandon D. Landers’s paintings, which I want to visit for a third time. The three of us stood in front of one of them for several minutes, noticing how the man and the woman who were portrayed in the painting were not alone. There was a third figure who had been “painted over,” but whose clothing was still faintly visible under the layer of black paint. I need to spend yet more time with this painting to be able to write a proper appreciation, but it is worth a trip to the Hammer in and of itself to see it for yourself. I usually look at work first before I read any notes put on a museum’s walls, and I had already noticed the frequent appearance of wall sockets in Landers’s paintings when I read a comment on a wall plaque that Landers made in response to a question about them. “I am the outlet,” he said, or at least that’s the way I remember his quip.

We were also impressed with the large-scale paintings of MacArthur Park by Jill Mulled as well as the recreation of Nicola L.’s sculpture that was meant to be interactive, but which we had to refrain from coming into contact with due to the lingering pandemic. Her sculpture, with its inversion of interior and exterior points of view and participatory subjectivity, would earn my vote as my favorite piece except that I think the vote would better serve a living artist, such as Landers.

I have jury duty this coming week, so I will not be able to schedule a visit to the Huntington until I have that obligation cleared off the table.

“Five Anthologies at the Hammer” — Photograph by Linda C. Fry

(Part Two)

Sometimes an anniversary happens to coincide with the cycle of one’s ordinary appointments in such a way as to give the interruption of routine an almost jovial hint of coincidence’s blessing.

This past week marked the 20th anniversary of Linda and me getting married, and I did not want the occasion to be reduced to a dinner out on that evening, so I proposed that we get away from the filthy air of Long Beach on our anniversary and we drive up to Santa Monica to enjoy some fresh air on the beach and get to hear the sound of waves. (Long Beach, contrary to its name, has only a long embankment of sand as the actual figure of its name; the breakwater in the bay forestalls any meaningful surf, and the water is disgustingly foul.) I furthermore proposed that we spend the night at the hotel we spent the single night of our honeymoon at twenty years ago. I was still a grad student back then and had to hurry back to the campus from our wedding in Thousand Oaks to resume my job as a teaching assistant as well as grading papers; so one night was all that could be spared.

We first went to Bergamot Station, where we saw a couple of galleries still very much in business. The painting that impressed me the most was Steve Galloway’s. I am familiar with his work, but want to see more of it as soon as possible. We then went to the beach, my first visit there in quite some time. Whenever I am there, it’s hard for me not to reflect on all the years I lived in Ocean Park and how frequently I would walk down near the spot where we were enjoying the mild sun and breeze.

The Embassy Hotel on Third Street in Santa Monica is now named the Playhouse, and we enjoyed our stay there very much. About a quarter century ago the Minnesota poet Jim Moore (whose book WHAT THE BIRD SEES I published in 1978) came to Los Angeles to read his poetry and he asked me to find a hotel that was not the standard cubicle. I don’t remember how I found out about this place, but he told me that it was exactly what he had fantasized. It’s been refurbished since those years, but it still retains a European ambience.

Staying overnight also had the advantage that driving to Dr. Chin’s office was a matter of a half-dozen blocks, after which we headed to the Hammer.

This is one of the photographs that Linda took of the room. This morning, the words “The Storyteller’s Chair” came to me as I thought about putting the photograph into the blog. And so it is.

(All photographs in this blog post are by Linda C. Fry, who retains the copyright and who has given permission for her photographs to be used in this blog post.)

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr