May 12, 2021

On May 12, 1991 Lee Hickman died. I remember that I was sitting at my desk in the apartment on Hill Street that I shared with my first wife, Cathay Gleeson, when Charles called and said that Lee’s struggle with AIDS was over. He asked me to write an obituary statement and send it out. I immediately got to work and soon after the Los Angeles Times more or less printed exactly what I wrote, though there was no byline.

I had first met Lee about twenty years before he died, and he became a mentor whose life I, in turn, affected. After I published his first book, GREAT SLAVE LAKE SUITE, and it was nominated by the Los Angeles Times as one of the five best books of poetry published in the nation in 1980, many people expected to see more increments of the six-volume project, TIRESIAS, that he had been working on since the mid-1960s.

Instead, he turned his energies primarily to editing. He told me once that my example of working as an editor and publisher had shown him a model of the cultural work that could be accomplished by a devoted individual. It was 40 years ago this coming September that I started working as the first poetry editor of BACHY magazine at Papa Bach Bookstore. When I left that magazine to start my own project, I suggested that John Harris take my place, and Harris in turn not only ended up buying the store, but appointing Leland Hickman as editor of BACHY. When BACKY ceased publication, Lee started BOXCAR magazine with Paul Vangelisti, and then launched TEMBLOR magazine as a solo project.

After Lee died, his poetry seemed to fall by the wayside, and I often worried that it would not get the continued attention it deserved. In the fifteen years after Lee died, my own life went through an economic and emotional ordeal that tested me to the limit. At one point, the best that I could do with a Ph.D. in Literature and all of my years of experience was a full-time job as an ESL teacher. In December, 2004, No one would even give me an interview for anything else. At age 57, I was being told that no one cared about what I had done or accomplished.

Perhaps it was a sign, though, that not all was lost. One day Linda and I went into NYC to visit Poets House, and I met Stephen Motika. We talked about Los Angeles poets, and I mentioned how much I still admired Lee Hickman’s poetry. By the end of the decade, I was helping Stephen edit a “Collected Poems,” which he co-published with Paul Vangelisti’s Seismicity Editions.

Lee’s poetry has continued to find enthusiastic readers. This past March, Stephen and I heard from Gordon Faylor, a poet and editor of the online publication Gauss PDF. He wrote that he had “recently acquired a copy of Leland Hickman’s Tiresias: The Collected Poems and adore it! Last year I was fortunate to find a copy of Hickman’s Great Slave Lake Suite, and so appreciate that Nightboat gathered all his work, which is otherwise so hard to find. I only wish he were better known—his writing is so astonishing and terrifying and beautiful.”

Thanks to the efforts of Gordon Faylor, as well as Quentin Ring at Beyond Baroque, one can now download a portion of a reading Lee gave at Beyond Baroque in 1984 (Barrett Watten also read that night).

Here is the link that will then allow you to download and listen to Lee reading his poetry.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1t-QgFyNFkkmBBsCee9oxQpxpbIwhcI2U/view?usp=sharing

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1t-QgFyNFkkmBBsCee9oxQpxpbIwhcI2U/view?usp=sharing

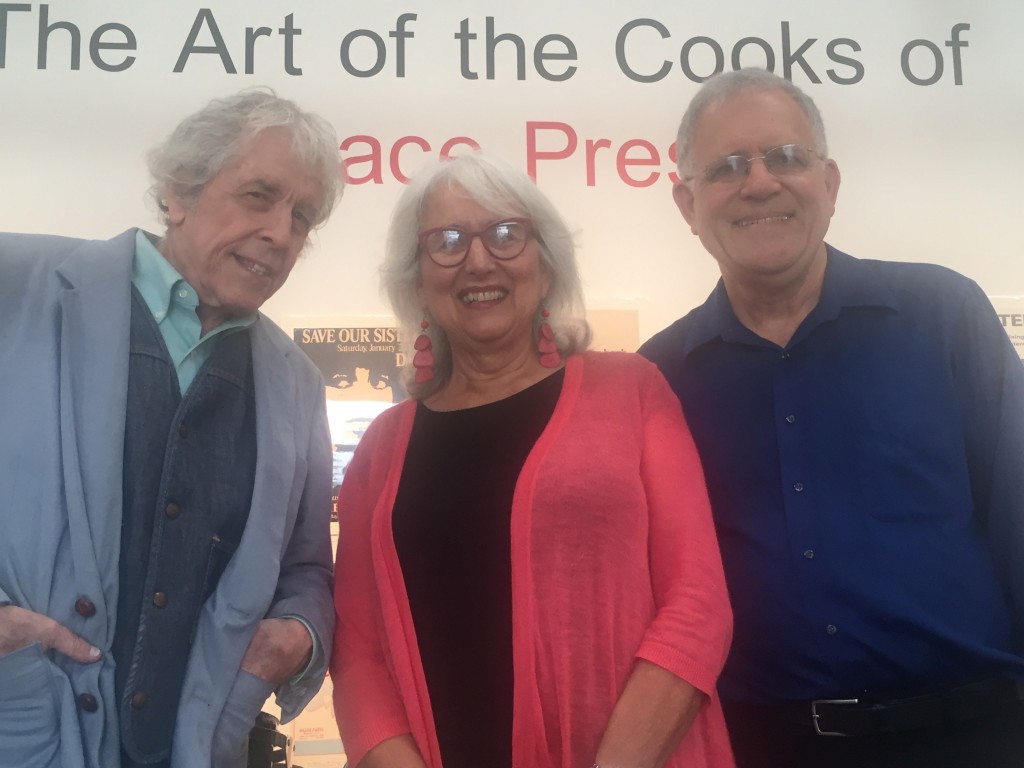

And, of course, my profound thanks also go out on the occasion of this anniversary to Stephen Motika at Nightboat Books, as well as to Dennis Phillips and Paul Vangelisti, whose friendship in Lee in the final decade of his life made an enormous difference to him.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr