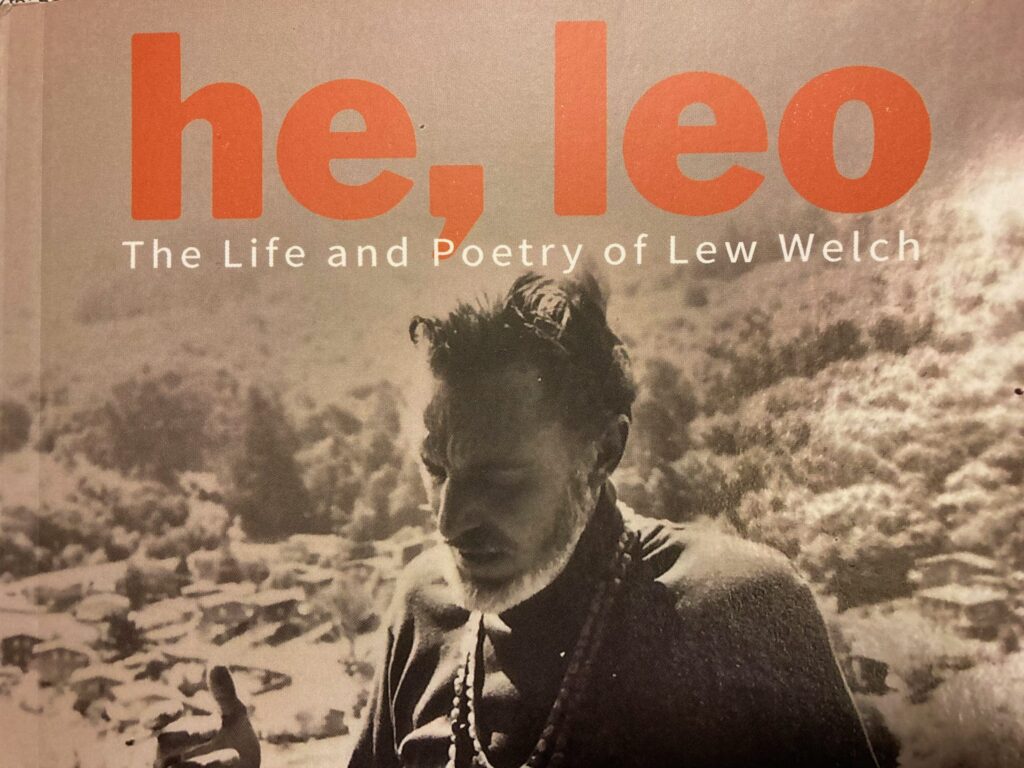

“He, Leo: The Life and Poetry of Lew Welch” by Ewan Clark

Oregon State University Press, 2023

In the early 1980s, a poet living in the Lone Pine-Bishop area of California invited poets working in the California Poets-in-the-Schools program to take part in a poetry festival. I’m not sure how she managed to get so many local schools to sign up as sponsors, though at the time the PITS program was still enjoying the benefits of poetry being a regular part of elementary school curriculum. Among the poets invited was Kit Robinson, whose choice of model poems included Lew Welch’s “After Anacreon,” which had been featured in Donald Allen’s NEW AMERICAN POETRY. I knew of Kit as a poet associated with the Language poets, and it surprised me that he was so enthusiastic about Welch. Perhaps, however, one thing that makes Welch such an intriguing figure is how he commands the attention of poets interested in very different templates.

Although RING OF BONE had been published just a few years after Welch had pulled the same “disappearing act” as Weldon Kees had done in the previous decade, Welch’s work has not subsequently gained the same kind of posthumous traction that Kees has achieved. Perhaps, some might argue, Kees produced a more substantial body of work. Even if one were to subscribe to that assessment, Welch has been massively underappreciated and I wish Clark’s book could have spent more time on Welch’s poems. Just now, for instance, reading “Song of the Turkey Buzzard,” I noted that one obvious comparison would be to Robinson Jeffers’ “Hurt Hawk.” For all I know, someone has written of it. If such is the case, it’s not mentioned in this book, and it would make a stronger case for Welch if it had been. I remain among those who admire Welch’s meditative lyrics. There are not that many poets who intermingle disparate complexities of emotional registers without indulging in rhetorical display.

That Welch deserves a biography might seem to the remnant of his surviving audience to be beyond dispute. On the other hand, it’s doubtful that anyone else will ever bother to put in the work needed to further bolster Welch’s standing in the Beat movement. Excellent biographies inevitably make a case for a sequel, and Clark’s biography is unlikely to inspire anyone to take on that task. Fortunately, Clark’s thorough inquisitiveness has at least filled in the story of Welch’s life sufficiently enough by including a large cast of Welch’s friends. Not least among the contextual evidence that Clark presents is his reminder that Welch took part in several important readings in the Bay Area. Welch, like Jack Spicer, was not in town for the famous Six Gallery reading, but Welch headlined several other readings with poets who participated in that reading, and his linkage with them as a peer deserves to be taken seriously. On the whole, Clark’s devotion to his poetic hero ends up rewarding his readers at unexpected junctures in Welch’s life; Clark is particularly superb at sketching the factors affecting those choices, including the crucial influence of Welch’s extended indulgence in psychoanalysis. On the literary side, Clark also digs up unexpected connections between Welch and other poets. How many contemporary poets would ever guess that Marianne Moore, for instance, was an ardent admirer of Welch’s poetry? I, for one, would never have suspected that Moore reviewed Welch’s work or corresponded with him.

In regard to the next point I want to make, I’m not certain that Clark had much of a choice. Sobriety would have saved Welch from his deplorable fate, and I confess that I find myself dismayed at how much Welch’s first biography ends up being a cautionary tale about excessive use of alcohol. I suppose if we can put aside his “expense of spirit in a waste of shame,” we can console ourselves with the knowledge that his best poems have the power to renovate our own lives and prevent us from succumbing to the stultifying psychic paralysis that is so endemic to American culture. Nevertheless, some readers will probably end up sighing as I did: “If only Welch had not spent so much of his youth living and working in Chicago on a job that forestalled his maturation as a poet!” Those were choices he made, nevertheless, and Welch’s endgame countenance and persona can no more avoid the consequences than those who lived more conventional lives.

One odd thing about the book itself is that it lacks any blurbs. While I am not a huge fan of such promotional gestures, they are often the only kind of critical response that a book receives, and Clark’s biography of Welch deserves to find its way to library shelves as well as the bedstead pile of general readers who remain curious about offbeat literary history. As such, therefore, here is my blurb:

“When the so-called Beat Generation first ruptured into public visibility, Lew Welch was far from being at center stage. During the decade and a half following the publication of “Howl and Other Poems” and “On the Road,” however, Welch reconnoitered with Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen and proceeded to produce a poignant body of work. Along the way, he was featured in some of the most important readings in the epicenter of the San Francisco scene and collaborated with Kerouac on a sequence of poems. While Ewan Clark’s biography does not flinch from recounting Welch’s false starts, it also delineates his vivid contributions to the chorus of Beat writing. In honoring Welch’s accomplishments as well as acknowledging his flaws, Clark makes the reader care about this poet as a triumphant survivor, at least in his poems, of one of America’s most turbulent periods of cultural renewal.” — Bill Mohr

**********

Kevin Opstedal wrote me after reading my entry on Welch, and with his permission I am adding a paragraph from his letter to this blog entry.

“Welch has been a very important poet to me ever since I first stumbled across his poems when I was in high-school in the mid-seventies. Since then, he has always been in the core rotation of poets I continually return to for inspiration & instruction. A poem such as “Wobbly Rock” is a masterwork, as is “The Song of the Turkey Buzzard.” He was also very important to other poets I have respected & was lucky to know personally, including Lewis MacAdams, Joanne Kyger, Philip Whalen, & Bill Berkson. Joanne was one of the editors of The Turkey Buzzard Review (a magazine published in Bolinas in the 70s) the title being an homage to Welch. I never got to see him read in person, but according to Joanne his readings were true performances. She told me once about a reading she was to give with Welch in the 60s. The organizers of the reading wanted Joanne to read after Lew. As Joanne related to me, Lew would sing & often cry during a reading & there was just no way anyone could follow that, so she insisted on reading first.” — Kevin Opstedal

***

Born and raised in Venice, California, and currently residing in Santa Cruz, Kevin Opstedal is a poet whose more than two dozen books and chapbooks include four full-length collections, Like Rain (Angry Dog Press, 1999), California Redemption Value (UNO Press, 2011), Rare Surf: Vol. 2 (Smog Eyes, 2006), and Pacific Standard Time (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016).The late Lewis MacAdams observed that Opstedal’s poems “are hard-nosed without being hard-hearted.” Among other anthologies, Opstedal’s poems appeared in CROSS-STROKES: Poems between Los Angeles and San Francisco, edited by Bill Mohr and Neeli Cherkovski.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr

One comment

Pingback: “He, Leo: The Life and Poetry of Lew Welch” by Ewan Clark | Koan Kinship — Bill Mohr’s Blog | word pond