August 3, 2025

Noah Davis at Hammer Art Museum, Los Angeles, California

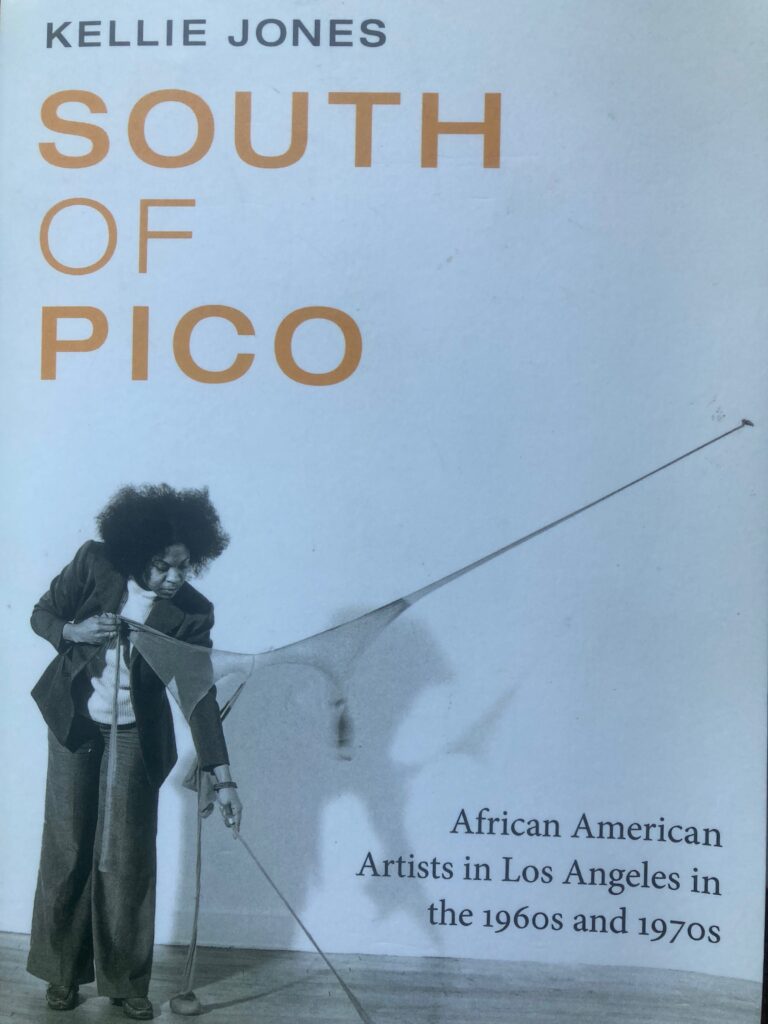

A little over eight years ago, MOCA presented an extraordinary exhibition of paintings by Kerry James Marshall, and I thought I would run the review I posted in this blog about that show again today, as I share a few notes and thoughts about an equally impressive show at the Hammer Museum right now: Noah Davis’s first major survey in any museum. Given that this exhibition will only be up for another four weeks, I wouldn’t want to delay anyone’s attendance by insisting that they first read Kellie Jones’s SOUTH OF PICO first, but I do want to insist that the only way to fully appreciate the cultural work that Davis undertook is to absorb at least some of the information in Jones’s examination of African American artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s.

Davis, along with his spouse, Karon Davis, was co-founder of the Underground Museum, a cultural space that was in the Arlington Heights section of Los Angeles. While the Underground Museum was not south of Pico, as such, it was as a cultural project aligned with the self-determined affirmations that marked the intermingled efforts of a cohort of mid-century African American artists in the years following the Watts insurrection. Now it may be the case that the essays of critical appreciation in the exhibition catalogue for this show at the Hammer Museum cite Jones’s book and bring it into their discussion of Davis’s work as a contextual jump-off point, but it would have been even better for the book to have received its own place of visibility to any visitor to this show. One of the first things that one should see before starting to see Davis’s work is the cover of this book. Not everyone can afford to buy the book, of course, but that’s what libraries are for, at least at the present moment.

On the whole, the placards commenting on the evolution of Davis’s poetics as painter are both pertinent and insightful. Basic information is not taken for granted, which is more refreshing than one might expect. Which painting was Davis’s favorite? This kind of question is always worth asking, whether it is directed to a poet, songwriter, or painter because it inevitably opens up the need to address provocative issues of cultural agency. It turns out that “The Architect” was Davis’s favorite painting, and looking at it reminded me of just how much white privilege props the narratives that fantasize about individualistic heroism. Ayn Rand’s protagonist in “The Fountainhead,” Howard Roark, is white. Whatever the challenges he faces might be, the one thing he doesn’t have to do is endure the indignity that Paul Revere Williams did of having to learn to draw upside down, so that he could present his sketches of proposals to white clients while sitting opposite them, since it would be unthinkable at that time for him to be allowed to sit alongside them. Howard Roark doesn’t have an expletive-deleted clue.

One of the most haunting images in the exhibition is of a “Single Mother with Father out of the Picture” (2007-2008). While the adults are the ones mentioned in the title, it is the young daughter whose suffering is most palpable. Her arm is in a cast, and it is not hard to deduce what has led the mother to tell the father to “hit the road, Jack, and don’t you come back no more, no more.” One doesn’t have to be a trained social worker to deduce that the domestic violence may certainly have involved some degree of sexual molestation. Even as David records this situation unflinchingly, he also was able to conjure up a level of mythic enchantment. “Year of the Coxswain” grapples with the heft required in the communal effort required to give meaning to our brief sojourn on the river run of eternity’s vast delta.

OTHER REVIEWS

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2025-06-16/noah-davis-ucla-hammer-museum

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/21/arts/design/noah-davis-painter-hammer-museum.html

*********

billmohrpoet.com

Sunday, June 25, 2017

Backlit by Blackness: Kerry James Marshall’s “Mastry” at MOCA

A couple of weeks ago, Hye Sook Park reported that Kerry James Marshall’s retrospective exhibition at MOCA was a must-see event. Even before her enthusiastic commentary, in fact, I had made a note in my memory’s calendar of the closing date of his show, which grew ever closer as the month has gone by. Getting time to see his show has not been easy: my teaching work glided straight from the end of the spring semester into the summer session course I am teaching without the slightest pause.

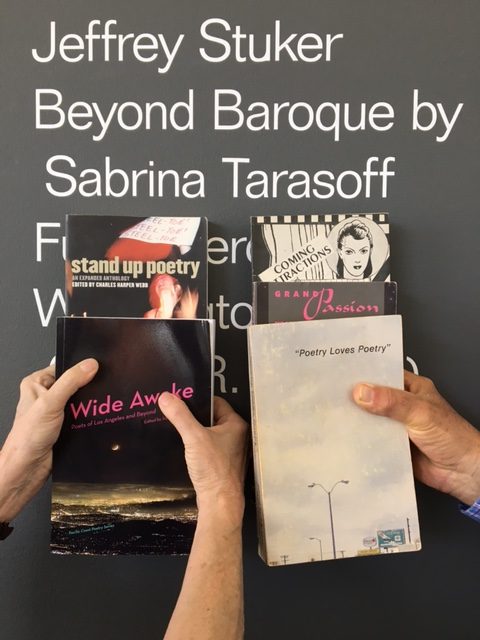

Two days ago, on Friday, we might have headed north, but on Thursday the place where my mother is being cared wrote me and said that her doctor would be visiting her on Friday; since I had never talked to him face-to-face in the past eight months, that priority cancelled any other possibility. We did drive up to Beyond Baroque that evening, though, and heard David St. John read from The Last Troubadour, and Christopher Merrill read an account of his long friendship with Agha Shahid Ali. As always, it’s a long trip from Long Beach to Beyond Baroque, but this time it was truly worth it. David is one of this country’s very best poets, and Christopher’s recollections made Ali a living presence in the room. I would have liked to have heard Christopher read some of his poems, too, but his choice to read a single piece made it all the more memorable.

On Saturday, with a rare empty square on the kitchen calendar, we saddled up and headed north. Marshall’s show is easily worth more than one visit, and I hope to return before it closes, if only to spend more time with an unframed painting from 2003 entitled “7 a.m. Sunday Morning.” Before I briefly talk about that painting, I want to list several pieces that impressed me almost as much: “Beach Towel”; “Slow Dance”; “Red (If They Come In the Morning”; “Frankenstein” and “Bride of Frankenstein”; “School of Beauty, School of Culture”; “Heirlooms & Accessories”; “Chalk Up Another One”; “Fingerwag”; and “The Actor Hezekiah Washington as Julian Carlton Taliesen Murderer of the Flank Lloyd Wright Family.” If I have not included the housing project paintings in this list, it is only because they have already drawn more than sufficient critical attention.

The scale of Marshall’s work is often startling in its acute depictions of personal identity within the encompassing hemispheres of economic and racial confinements. Circling in a room of fermenting ordinariness, the figures in “Slow Dance” are both holding tight to each other’s poignant desires for more than has been allotted them, and grateful that at least they have each other for the moment. It more honestly addresses the romantic plight of marginal individuals, no matter what their race, than any painting I have ever absorbed into my memory.

The room the dancers inhabit is exactly what could have been foreseen by anyone who looks closely at the furniture of an engagement scene in a cheap restaurant. Even if one imagines the couple looking back at each other, and then unclasping to reach for a celebratory sip of their drinks, one would hardly expect either one to feel more comfortable in the minimally padded chairs the restaurant has provided them. Their fond ebullience is as much a performance meant for themselves as the onlookers they are posing for. The mise-en-scene of the restaurant extends to the smallest details of an urban backyard: the pink flip-flops being worn by the sunbather in “Beach Towel,” for instance. Equally pertinent in scope, one should not overlook the oversized earrings of “Fingerwag.” Marshall has a profound ability to augment his excavation of that which the ideological normative would prefer not to be present at all.

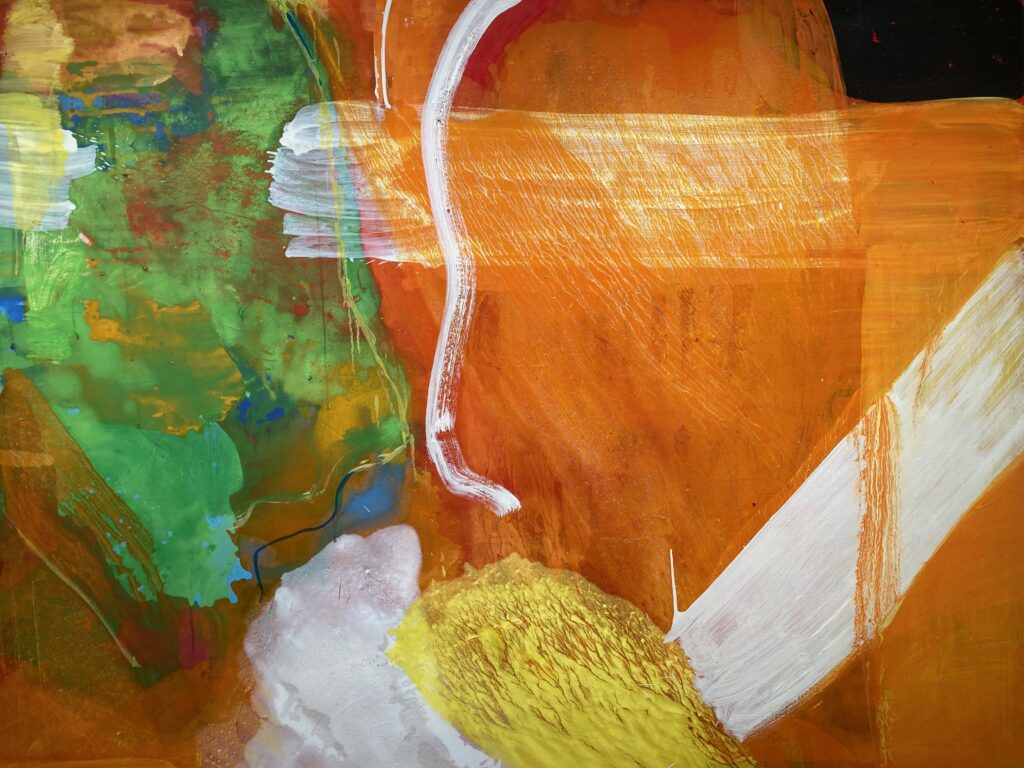

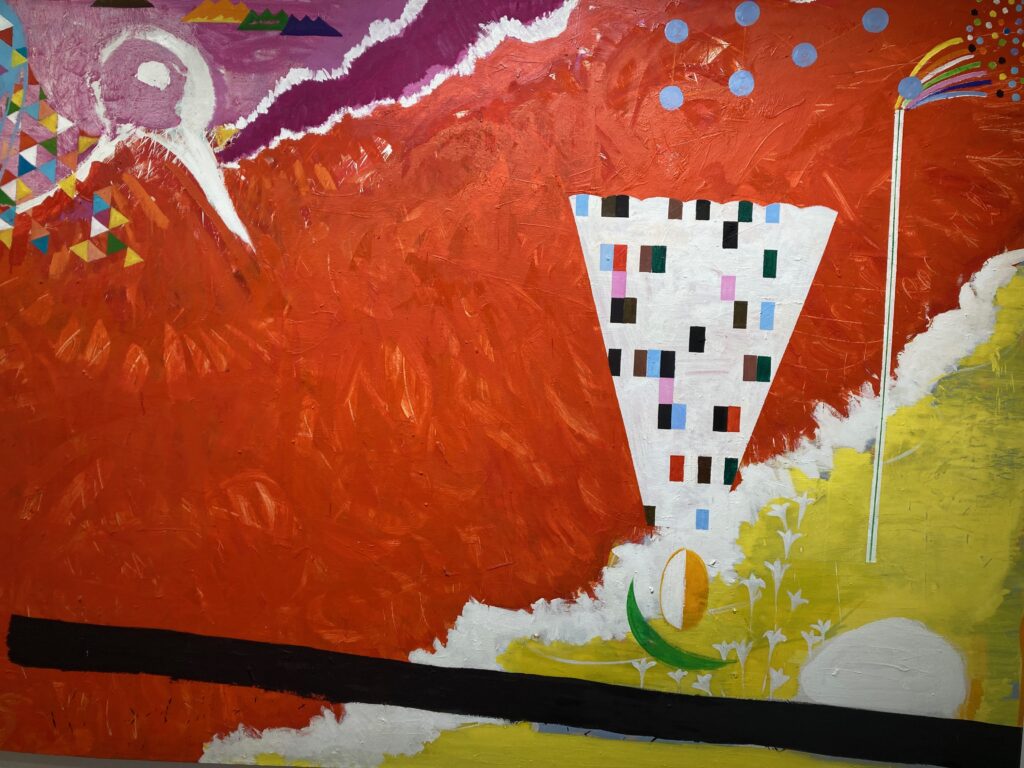

Jed Rasula mentions the contrast between “the politics in the poem, and the politics of the poem” in his intriguing study of American poetry anthologies. One could use the same distinction to talk about Marshall’s work, too, since in his case the politics in a painting such as “Red (If They Come in the Morning” are equally about the cultural politics of abstract painting and its reluctance to accept work done in that domain by African-American painters.

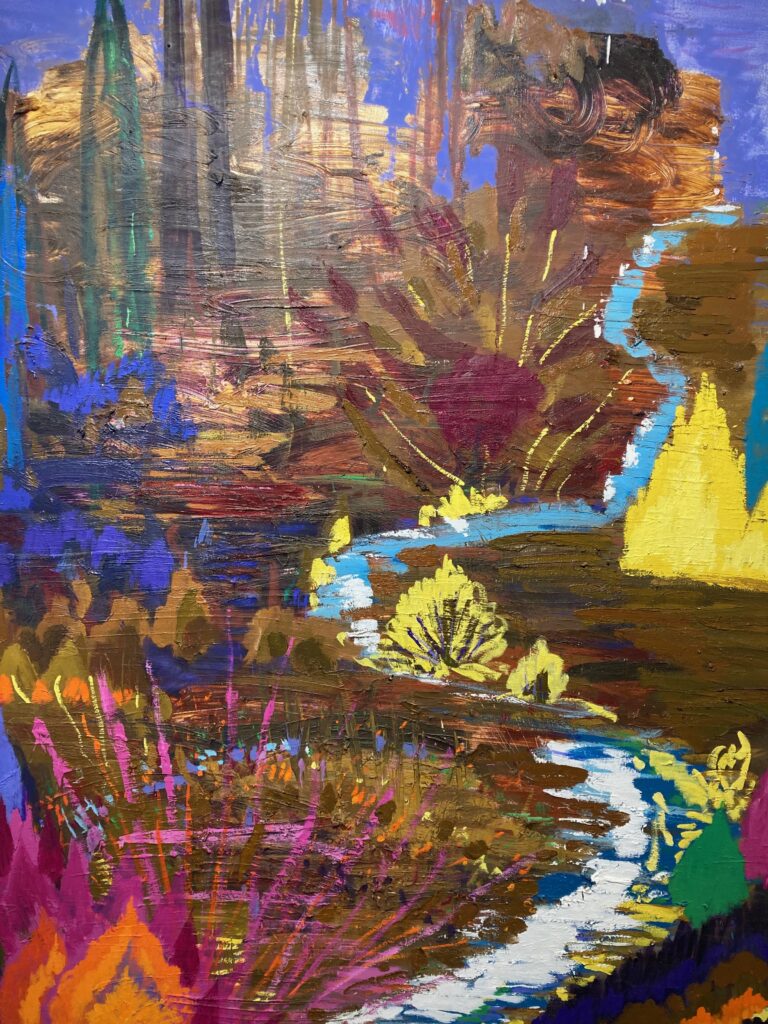

The street scene depicted in “Sunday Morning, 7 a.m.” has no overt politics, and yet the speeding white car that the running child seems to avoid by not much than a second and a half can hardly be separated from the more obvious repression cited in “Chalk Up Another One.” The adults in the post-dawn background stay safely on the sidewalk with its immediate access to the liquor store. The child has other comforts in mind. What might await that young man is hinted at in the right hand portion of the painting, in which Marshall’s synaesthetic handling of urban light portends some future visitation. Softened by a prismatic uncertainty, as if a late spring day will fulfill its potential for revelation, one can almost hear Whitman’s pure contralto sing the organ loft of some unanticipated destiny. Redemption is not an option, so don’t get carried away with hope, this light suggests. On the other hand, there is no reason to settle for mere survival of one’s ideals.

This show will be up through next weekend. As hard pressed for time as you might be, make every effort to catch this show. I agree with Christopher Knight’s concluding assessment in the LA Times: “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” is the first time in a long time that MOCA’s exhibition program has felt essential. Don’t miss it.”

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-kerry-james-marshall-moca-20170320-htmlstory.html

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr