Monday evening, October 14, 2019 — 9:40 p.m.

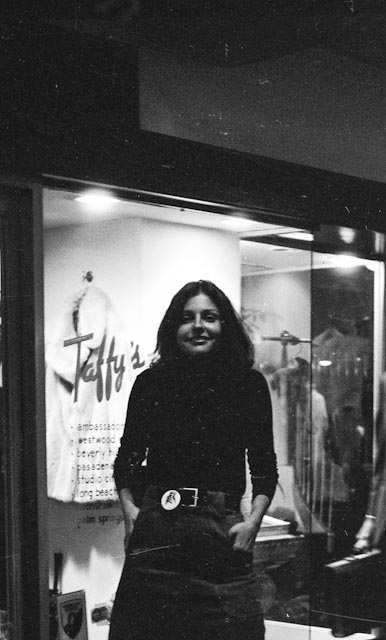

(photograph of Kate Braverman, (c) Rod Bradley)

About a dozen minutes ago, I was sitting on a sofa in the living room, grading the mid-term examination that I gave several dozen students in my “Survey of Poetry” course this afternoon. I was wondering if I had done enough for the evening when I heard Linda’s phone ring in the bedroom. At first I thought I heard Linda say it was a wrong number. If only it had been; instead, I heard the very sad news from our friend Laurel Ann Bogen that Kate Braverman died.

It’s been years since I’ve seen her. Maybe over 20 years. I think the last time I talked with her was at Dutton’s Bookstore on San Vicente Boulevard. We talked briefly about Lee Hickman, with whom both of us had very close relationships. Kate was one of the founding members of the Momentum poetry workshop, a hand-picked group of poets who met in each other houses and apartments back in the mid-1970s. We had all at one point or another been part of the Venice Poetry Workshop at Beyond Baroque earlier in the decade, but had grown impatient with poets who were unwilling to read the variety of poets we were curious about. In addition to Kate, Lee, and myself, the other members of the workshop were Jim Krusoe, Harry Northup, Dennis Ellman and Peter Levitt. These seven poets formed the majority of the poets in my first anthology, The Streets Inside. Of all the poets in the group, Kate was the one who most benefited from the criticism we gave each other. She was the most gifted of all of us in terms of having nimble access to an imagination overbrimming with lyricism. To this day, I don’t believe I have ever met anyone who is as gifted as she was.

To the best of my recollection, I was the first editor in the United States to publish Kate’s poetry. Kate was an ambitious poet, though, and certainly wanted her poems to be in the best known magazines at that time. Within a few months of that publication (the third issue of Momentum, 1974), she had poems accepted by the Paris Review. Not only did I continue to publish her work in Momentum magazine, however, I also published her first book of poems, MILK RUN. Reviewed in the Los Angeles Times by Ben Pleasant, the first run sold out fairly quickly, and I printed another 500 copies. I may not have published as many books as other independent presses did back then, but I somehow had a quirky ability to select poets who were destined to make an impact.

Kate and I stayed friends through most of the 1970s, though my suggestions for cutting the first draft of Lithium for Medea were not well received. “You’re not my editor and you’re not my friend.” The final version, in fact, reflected many of the changes I had suggested, though I believe her editors were the ones who finally coerced her into trimming the book.

Although I included Kate’s poems in my second anthology, POETRY LOVES POETRY, we rarely saw each other any more. Not too long after that she left Los Angeles for good, and only returned intermittently. The only person I knew who was in personal contact with her in recent years was Rod Bradley, who took the photograph that appears at the start of this blog entry. After a recent visit with her, he told me that she felt completely ignored by the American literary establishment. That may well be, although I suspect that Kate was at least partially responsible for that disregard. She saw no reason to compromise, at least when she was young, and why should she change? Writing sentences that oozed the scintillating excesses of color’s exquisitely warped reverberations was all she ever cared about. If you didn’t want to dance to it, then take your drum kit somewhere else. She didn’t need you to tune her guitar.

At this point, I have to begin writing an intimate memoir of that time. If I can bring myself to give a full account, I only hope that I can convey the tender respect I still feel for Kate. It may be another thirty years before she gets the recognition she wanted so badly, and truly deserved. But her work is destined to have a devoted coterie until that time arrives. Don’t worry about joining the posthumous parade of her new fans. There won’t be as many as you might imagine. It takes courage to be one of her readers. Almost as much courage, in fact, as it took her to write without flinching of the startling metamorphosis of her own incantations.

Post-Post-Script (in reverse order!)

Having posted a short set of links to Kate’s writing, as well as the first official report of her death, I am now wondering if I feel more protective of Kate or of myself. As I think back on an oral history interview that UCLA’s special collections conducted with me three or four years ago, I don’t recollect how much detail I went into about Kate, or about any of the poets I knew back then.

I know that I didn’t talk about her brief experience as a poet-in-the-schools. Although Kenneth Koch made it seem as if this introjection of living writers into K-12 settings was a NYC innovation, the idea actually derived from a small group of poets and teachers working in the San Francisco area. By the early 1970s, it was spreading throughout the state of California, and by 1974 the late Holly Prado had been hired to serve as regional coordinator in the Los Angeles area. In the spring of 1975, Kate and I were assigned to work together at a high school in Redondo Beach. On the first day, we talked about poetry with the students and read a few of our poems as well as giving them a chance to write and read their own work. Kate’s choice of a poem about her menstrual cycle might have pleased radical feminists for its topic, although they would have demurred about her admission of the degree of vulnerability that having her period generated. High school students were not quite ready for the candor of Kate’s poem. I got a phone call from the school a few days later in which they asked me to come back to the school, but not accompanied by Kate.

In retrospect, of course, I can’t help but wonder if Kate knew perfectly well what the outcome of her choice might be. In one of the interviews in the links below, Kate emphasized how much she saw writing as a highly charged transgression. Writing was akin to criminality, and to that extent one of the writers that Kate probably should be more often compared to is John Rechy, whose writing will most certainly not become canonical assignments at the average high school.

I never knew Kate to have any other job other than writing. I always assumed that Kate managed to extract from her mother enough support to pay the rent, buy food, and drugs. It was a contractural relationship, however, in that Kate had little choice but to work on a novel. If poems were a means of establishing an initial reputation as a writer, my guess is that Millicent Braverman (“the original barracuda,” was one phrase bestowed on her from that period, though not by me) made it clear that Kate was being subsidized so that she could produce work worthy of a NYC publisher’s imprint and reviews in all the important outlets. My recollection is that the arrangement got rocky at times, and Kate’s mother would pressure her to get a job. “Fine,” said Kate, and went out and got a license to drive a cab. One afternoon, at her apartment on West Washington, she pointed to the license taped to the kitchen wall and recounted her mother’s curt refusal to go along with that plan. Kate insisted that driving cab was the only job she was interested in. After all, our fellow poet and Momentum workshop member Harry Northup had driven a cab for a year before he got his role in Martin Scorsese’s film about a deranged taxi driver in NYC. And did not Lew Welch have a poem about driving a cab in Donald Allen’s anthology? Those were hardly convincing examples of how safe Kate would be driving a night shift in Los Angeles. Braverman’s mother gave in, and Kate was quickly back to work at her typewriter.

Post-Scripts:

Tuesday, October 15, 2019; 7:45 a.m.

I have spent the past hour digging around for links to interviews and articles. The one that will give the best sense of the Kate Braverman I knew in Los Angeles in the 1970s is in the Brooklyn Rail.

https://brooklynrail.org/2006/03/books/kate-braverman-with-lisa-kunik

http://www.bookslut.com/features/2006_02_007804.php

http://www.full-stop.net/2018/05/31/reviews/lauren-friedlander/a-good-day-seppuku-kate-braverman/

https://www.latimes.com/obituaries/story/2019-10-14/kate-braverman-poet-author-obituary

Sunday, October 20, 2019

The New York Times also posted an obituary this week, which I found in the Sunday print edition that arrived at my residence.

NOTE: The NY Times obituary failed to provide enough detail in describing Kate Braverman as a “founding member of the Venice Poetry Workshop.” If by “Venice Poetry Workshop,” the NY Times is referring to a splinter group that met in the Old Venice Jail (now SPARC) forty odd years ago, then perhaps she could be accorded the status of founding member. If, however, the NY Times is suggesting that Braverman was a founding member of Beyond Baroque’s Wednesday nigh poetry workshop, which was always informally thought of by the community in the mid-1970s as THE poetry workshop in Venice, then Braverman was closer to being a younger sibling of the first wave of poets who took part in Beyond Baroque’s maturation as a cultural institution. The Beyond Baroque poetry workshop was founded by Joseph Hansen and John Harris soon after Beyond Baroque’s founding in 1968, and by the winter-spring of 1973 had attracted poets on Wednesday evenings to its storefront setting, near the intersection of Venice Blvd. and West Washington Blvd. (now Abbott Kinney Blvd.), as diverse as Frances Dean Smith, Eleanor Zimmerman, Ann Christie, Harry Northup, Jim Krusoe, Lynn Shoemaker, Leland Hickman, Dennis Ellman, and Paul Vangelisti. The earliest that Kate could have shown up would have been in late, 1973.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr