March 14, 2016

Scott Wannberg – The Official Language of Yes (Percival Press; 2015)

I bought my copy of Scott Wannberg’s first comprehensive posthumous collection of poems a few months ago at Beyond Baroque and have been squinting at it ever since. Sad to say, the printer in Spain must have diluted his ink until it was a pale gray. As a result, it is hard to read this book for more than a half-hour. I hate to begin this commentary on a book that deserved, at the very least, a nomination for a major award with a complaint about the production, but I was talking to one of my oldest poetry friends around Christmastime and both of us felt the same way about this book’s legibility.

It’s always possible that the faded quality of the ink may have reflected a commitment to more ecologically friendly printing practices, but in that case the choice of paper should have been made more carefully. The odd part is that the printer seems to be the same outfit that produced Wannberg’s earlier collections by Percival Press. One can pick up Strange Movie Full of Death (2009) and glide through the poems without one’s eyes feeling exhausted after ten minutes. In Strange Movie, the ink is solidly embarked on the page and one’s eyes sway gently along. Perhaps a warning note of what transpires in Official Language can be seen in tomorrow is another song (2011); the ink seems to hint at a recessional in thickness. Nevertheless, tomorrow is still an adequately printed book. Official Language disappoints in the puzzling fuzziness of its presentation.

My disappointment in the production aside, The Official Language of Yes serves as a generous grab-bag of poems by a prolific poet who blurs the distinction between Beat and post-Beat. Wannberg is one of those rare poets who refuses to play the language game on any other terms other than an all-out resistance to accommodation. Wannberg’s poems often simmer with a comically contumacious anarchy. If the world is led by self-serving fools, Wannberg not only undercuts their pretensions to legitimate authority with his deft mockery, but shows how to hold up and keep dancing despite being under modernity’s repressive pressures. At times ungainly, his poems almost always regain their inner balance and often pivot and romp in an affirmative celebration of life’s droll absurdities. Whatever his subject of choice at the moment of composition, one finishes the poem nourished by a quirky, elevating humor.

THE 3 THINGS

three things are needed.

a space big enough to die in called privacy

someone’s phone number other than my own

the feeling that no matter how many muscles I make

I remain

vulnerable

EINSTEIN AND THIS GIRL

Einstein and this girl

in a Mexican restaurant

debating the firmament

called time

how it hangs over them

an older brother threatening

to leave but never finding

the room to do so

I don’t remember when I first met Scott Wannberg. My guess is that it was at Vroman’s Bookstore on the Santa Monica Mall. Even back in the early 1980s, Wannberg had already become a kind of literary magician as a book clerk, imparting a month’s worth of cultural aplomb to any customer curious enough to ask for a book recommendation. One rarely left the store with only one book in hand. Scott should have worked for commission. He was a literary matchmaker, and the blind dates were always memorable. It wasn’t just individual readers and books that Scott brought together. He was a single degree of separation between a vast number of people in Los Angeles who were otherwise strangers. In knowing that he was our guide when we went to Dutton’s Books on San Vicente Blvd., we knew we were part of an improvised library of uncommon devotion to the written word. There might well have been someone like him in New York, London, or San Francisco, but I doubt it. To engage with Scott at Dutton’s was to experience a theatrical causerie.

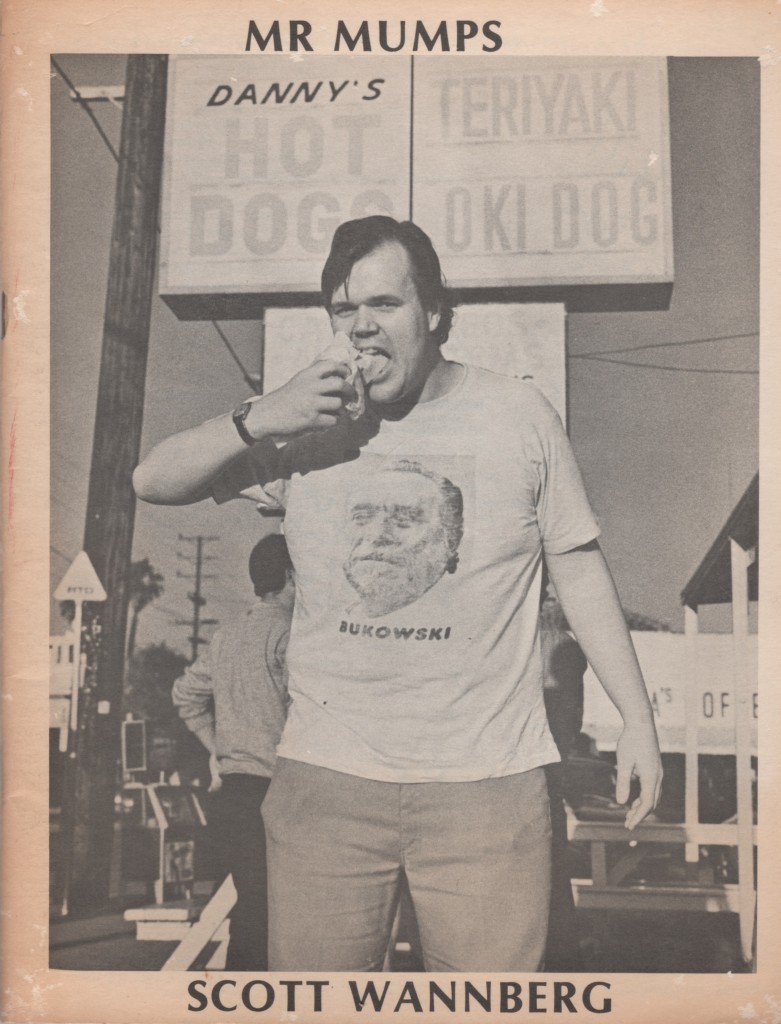

If I don’t recollect personal history, I do remember, however, my sense of dismay when I was about to take “Poetry Loves Poetry” to the printer in the summer of 1985. There were over five dozen Los Angeles-based poets in that anthology, but Scott Wannberg was not one of them. To this day, I’m not certain how that could have happened. It wasn’t for lack of access to his writing. I had a copy of Mr. Mumps, his first collection from Ouiji Madness Press. In fact, the copy is signed with a nod towards Momentum, the magazine I edited and published in the 1970s:

“For Bill, who was the first stevedore of swing to put my nectarine of a name in print (&) who deserves a rainbow of resonance for his energy & love & passion. The birthday tonight is among happy strangers.” – Scott 5/28/82.

Mr. Mumps is definitely not part of the accessible canon. Only two libraries in the entire United States have a copy of it, and both are in Northern California. Mr. Mumps features 34 poems, several of which should have been in “Poetry Loves Poetry.” How could I have passed up the opportunity to anthologize “They Came from Beneath the Planet of the Moral Majority.” “Smiling Samurai,” and “Another L.A. Poem”? I have often had people tell me that “Poetry Loves Poetry” is one of their favorite anthologies, and it still holds up for me, but Wannberg’s absence remains an inordinate lapse.

Perhaps his absence from “Poetry Loves Poetry” addresses the distinctiveness of Wannberg’s poetry. It is not so much that he serves as another instance of that classic buttress of marginality, the poet’s poet, as he is the poet who refuses to be other than a poet. There is an acceleration in Wannberg’s writing that concedes nothing to the career imperatives of being on the judicious wave-lengths of social feasibility. Wannberg, as far as I can tell, never courted editors or publishers or attended events in hopes of securing some spot for himself in the sticky carnival of popularity. He is not the only such case of self-effacement in the literary realm, but he is the one most affectionately remembered by those such as myself who should have done more to call attention to his work when he was alive.

It gave me special pleasure, therefore, to be able to include a substantial number of sections from a long poem by Wannberg in the recently published anthology, Cross-Strokes: Poetry between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The poem has a very long title: “the cat put me out last night just before world war III came strutting down my street to angrily knock onmy door and demanded that i tell it what the hell i meant when i gave my dog my car keys and said here, you take care of business for awhile.” It is possible that there are other major, substantial poems about the murders of Harvey Milk and Mayor Moscone in San Francisco on November 27, 1978, but this may be one of the few that will still be worth reading a half-century after the assassinations.

Wannberg was a vigorous and lively reader of his poems, yet he never found himself counted among the spoken word poets who rose to prominence in the early 1990s, nor was he included in the Stand Up poets with whom he shared a common ambidexterity of seething wit and soothing emancipations. Perhaps one cannot feel completely freed of self-imposed burdens, after reading his poems, but the abjection is less confining. Consider the role of servitude in the following poem, for instance:

WINNERS AND LOSERS

The Winners are coming over for dinner.

They will expect you to put out the best silver.

The Losers are eating very fast.

They have to be gone when the Winners pull up in front.

The Losers will get indigestion from eating so fast.

The Winners on the other hand, will take hours to get

through a simple meal.

I’m jus the kitchen help.

Apparently I have no life other than making sure

the best silver is properly used.

The Losers, well, I like them a lot better.

They eat with their fingers. And they bleed just like me.

The Winners never bleed.

They are insufferable.

The Winners always get my name wrong,

even when I wear a name badge.

Being Winners, they feel no obligation to call me by

my right name.

The Losers, they drink a lot, and being full of drink,

take great pains to say my name the right way.

It is a thing of principle with them,

to be very drunk, and still be able to say my name.

Sometimes I have no name.

Sometimes, I have many names.

The Winners never really see me.

The Losers see me too much.

There has to be some place in between

where things just go, jell, and do.

There has to be some place

where the lovers never have to win or lose.

There has to be some heart

at work.

(“The Official Language of Yes,” page 145)

Any number of poems get published every day in the United States that could make an official claim to be more elegantly composed or strewn with subtle intricacies. There is little use in remonstrating the abundance of idle imagination put to use on self-indulgent themes, however; far better to acknowledge that time is getting short, and in that oncoming brevity to turn to Scott Wannberg’s poems as a way to hold fast to the slim chance of a redemptive chorography, one with a “heart / at work.” All the whimsical line-breaks in the world are of little help if a poet lacks the heart to say what must be said if this planet’s chief tenants are to pull themselves back from the precipice.

* * *

Finally, those who read my blog on any steady basis might recall that I wrote about the peculiar absence of Bob Flanagan from the “Stand Up” poetry anthologies that Charles H. Webb edited between 1992 and 2002. The omission of Scott Wannberg is equally puzzling. Maybe more puzzling. After all, Flanagan did become better known as a performance artist in the final third of his life. Wannberg was a poet who was constantly visible as a poet throughout his life. Academic poets, it would appear, like to imagine that there is no longer an “underground” in American poetry. Such an erasure only reinforces the suspicion of those in that underground of how woefully incapable many people are when it comes to reading out of a narrow comfort zone.

For those who are working on anthologies of poetry and who are tired of the same old roster, I would suggest typing up Scott Wannberg’s “of the people, by the people, for the people…” and taping a copy of it on the door to your workroom. Let your anthology build itself around Wannberg’s indefatigable alacrity.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr