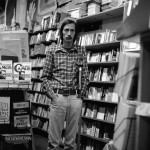

THE KID IS THE ULTIMATE MAN: Bob Flanagan (1952-1996) and Sheree Rose

Today is the 20th anniversary of the death of Bob Flanagan, although this post happening to appear today is the result of pure accident. The photograph of Flanagan accompanying this post is from a set taken by Rod Bradley at a publication event for issue number 11 of Bachy magazine at Papa Bach Bookstore in the mid-1970s; I spotted the CD Bradley had given me with the photographs at my office last week and took another peek at them over the holiday weekend, at which point I decided to start work on a long overdue tribute to Bob Flanagan and his artistic collaborator, Sheree Rose. When I looked up Bob’s dates to get an exact bearing on his chronology, I found the anniversary of his death to be rapidly approaching, so I redoubled my efforts. It should be noted, by the way, that the title of this post is a reference to the words on the cover of a book in the lower left hand corner of the photograph.

Flanagan began reading his poems around Southern California beginning in the mid-1970s, when he was still in his early 20s. In point of fact, I attended a festival of poets that included Flanagan in what had to have been his first reading in any venue that got public attention whatsoever. The “festival” took place in an unfinished, multi-story office building somewhere near downtown Los Angeles. I suppose it would be possible to dig through my archives and find the name of the hapless organizer and the exact address, but this was not an event that merits much more citation than Flanagan’s appearance, which stood out because of the contrast between his earnestness and the abundance of clichés in his poems. Flanagan was not born with a natural flair for vivid imagery. I distinctly remember listening to him read at that festival and thinking to myself that he had as little talent as any young poet I had ever heard. The old truism that talent is mostly hard work is certainly demonstrated in Flanagan’s case, for it was due to his determination to become a good writer that he matured into one of my favorite poets. In addition to his willingness to work very hard at becoming a better writer, he also had the advantage of being a member of the Beyond Baroque workshop, where poets such as Jim Krusoe and Jack Grapes continued his education in poetry outside of the academy.

I published some of his poetry in Momentum magazine and was impressed enough by his first book, “The Kid Is the Man” (Bombshelter Press, 1978) to write a review of it. It was the first formal public notice that Flanagan’s writing received. “The Kid Is the Man” contained all of the poems that Flanagan had made famous within several coteries at work in Los Angeles back then. “Love Is Still Possible” and “The Bukowski Poem” remain two of the earliest instances of poems that deserve to be in the Hall of Fame for the Stand Up school, a point to which I will return in a moment. Nor did Flanagan cease to write poetry even as he increasingly began to focus on music, theater, and performance art as outlets for his creative impishness and considerable wit, not to mention his legendary masochism. When it came time to choose his poems for Poetry Loves Poetry (1985), the work was all from the period after his first book was published and included another stand-up classic, “Fear of Poetry.” He went on to publish several collections, including “The Slave Sonnets” and a superb collaboration with David Trinidad, “A Taste of Honey.”

Given all of this poetry by Flanagan and the degree of his visible presence through frequent readings in Los Angeles, it is astonishing to realize that he is absent from all three editions of “Stand Up Poetry,” the first of which appeared in 1990 as a project co-edited by Charles Harper Webb and Suzanne Lummis. I suppose one has to take on faith the sincerity of the editors when one reads in the first slim volume (84 pages) that the 22 poets appearing in the book are merely representative of the Stand Up poetry movement and are not intended to be seen as the essential members of its first wave. However, Flanagan does not appear in either of the subsequent volumes, either. In fact, Flanagan is also absent from “Grand Passion,” which was also co-edited by Webb and Lummis, and which appeared in 1994, while Flanagan was still alive.

I find Flanagan’s absence from this evolving series of anthologies to be nothing short of astonishing, especially since Flanagan had a generous selection of poems in my anthology, “Poetry Loves Poetry,” which appeared in 1985 and which contained the poems of Webb and Lummis, too. In other words, his work was right there in front of them. Now it’s true that by 1990 Flanagan was primarily known as a performance artist, but he was still active as a poet. In fact, Flanagan was one of the primary poets who ran the Beyond Baroque poetry workshop between 1985 and 1995. Despite the way that his notoriety as a “Super-Masochist” began to overshadow his poetry, I certainly regarded Flanagan as worthy of consideration as a working poet in the early 1990s; and when I asked him to be a guest on my poetry video show, “Put Your Ears On,” he did not hesitate to accept. It turned out to be one of my most successful shows. We had a monitor on stage with a video of David Trinidad reading his lines from A Taste of Honey that alternated with Bob reading his lines live in the studio. His wit was on full display: when I asked him if he ever considered moving to NYC, where he had been born, he responded that he “preferred his creature comforts, and New York is mostly creatures.”

In addition, his poems in “Poetry Loves Poetry” were among the very best one in that anthology. “Fear of Poetry” remains a classic example of a metapoem that should be studied by every young poet. It should also be mentioned that Flanagan’s prominence within the poetry community in the mid-1980s because his lover and artistic collaborator Sheree Rose was a very fine photographer. When I decided that full-page photographs of the poets should be included in “Poetry Loves Poetry,” it was Sheree Rose who drew the assignment of persuading several dozen poets to relax enough to let their private masks become somewhat visible in a public portrait. She did a superb job and I hope some day that Beyond Baroque can have a retrospective of her work.

Finally, to square the paradoxical circle of his absence, I would also note that Flanagan studied at California State University, Long Beach, where Gerald Locklin taught for 40 years. Locklin and his colleague Charles Stetler are the poets known for using the title of Edward Field’s book, Stand Up, Friend, with Me, as the basis for a moniker to describe a kind of poetry that became increasingly popular in Southern California in the years after the Beat scenes in Los Angeles and San Francisco began a period of diminishing returns. Both Locklin and Stetler are in the first volume of Stand Up Poetry, along with another CSULB professor, Eliot Fried, whose poetry I had also published in the first issue of Bachy magazine in 1972.

The line-up of poets in the first volume of “Stand Up Poetry” (Red Wind Books, 1990) is very impressive: Laurel Ann Bogen, Charles Bukowski, Billy Collins, Wanda Coleman, Edward Field, Michael C. Ford, Elliot Fried, Manazar Gamboa, Jack Grapes, Eloise Klein Healy, Ron Koertge, Steve Kowit, Jim Krusoe, Gerald Locklin, Suzanne Lummis, Bill Mohr, Charles Stetler, Austin Straus, Charles Webb, and Ray Zepeda. There are also two poets named Ian Gregson and Viola Weinberg. That the poems of Bob Flanagan and Scott Wannberg should have been there in place of Gregson’s and Weinberg’s is obvious now.

The importance of Bob Flanagan’s writing and art and of his collaborations with Sheree Rose recently was recently confirmed by the acquisition of his archives by the University of Southern California. You can access information about that archive at:

http://one.usc.edu/bob-flanagan-and-sheree-rose-collection/

On the 20th anniversary of his death, I would urge those who are looking for material to analyze through the lens of disability theory or queer theory to consider visiting that archive and to get to work. In doing so, it would also be worth remembering that Flanagan is an exemplary Stand Up poet and one of the primary members of the original core group. Those of us who were here in the early and mid-1970s know the accuracy of that statement, even if editors who didn’t arrive in Los Angeles until the late 1970s prefer a version that might reflect a fear of being tainted by Flanagan’s transgressive art. In equally emphasizing his stature as a Stand Up poet, critics might also consider how his writing fits within the Confessional school of poetry, which is all too often viewed as a movement with no important contributors after 1980. How about someone taking on an article with a stark contrast: Sharon Olds versus Bob Flanagan. Now that would generate an incandescence worthy of the audacious risks that Flanagan took and lived to tell about, far longer – decades longer – than anyone ever suspected he would, even those of who feel very lucky to have heard him read his poetry or to offer up his body to the demons of pain. Suffering is not redemption, but it is hard to know what is worthy redeeming if one does not suffer to test those boundaries. Flanagan’s art and poetry offer us a chance to redraw our boundaries and set off anew.

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr