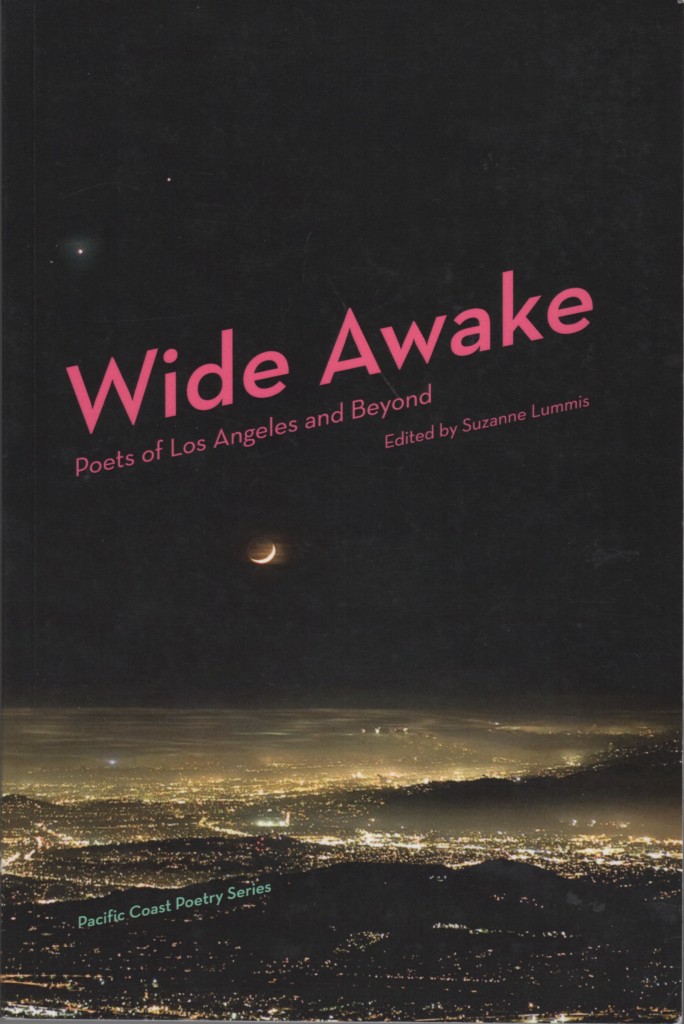

Beyond Baroque was founded by George Drury Smith a half-century ago as a publishing project. When the initial issue of its magazine faltered, the building that housed the printing equipment also became a refuge for a poetry workshop and other improvised cultural events. The magazine regrouped, and eventually achieved a substantial circulation in a newsprint version. In the mid-1970s, stand-alone collections of poetry were published by poets such as Maxine Chernoff and K. Curtis Lyle, as well as Eloise Klein Healy, who would go on to become L.A.’s first poet laureate. In the century’s final decade, under Fred Dewey’s direction, a series of books appeared by poets such as Eve Wood. Earlier this decade, Los Angeles poet Henry Morro inaugurated a new series of Beyond Baroque books, directed by a collective committee, under the imprint of the Pacific Poetry Series.

The most recent selection is Carol Ellis’s LOST AND LOCAL, which will be officially published with a debut reading on Saturday, December 14th at Beyond Baroque, at 8 p.m. Ellis received a Ph.D. in English from the University of Iowa with a dissertation on James Wright. She subsequently taught at several colleges in California, and now lives in Portland, Oregon. Her writing has appeared in ZYZZYVA, Comstock Review, The Cincinnati Review, Saranac Review, and Cider Press Review; her chapbooks are HELLO (Two Plum Press, 2018), and I Want a Job (Finishing Line Press, 2014). I wrote a review of the latter title, which appeared in

Suzanne Lummis, one of the major editorial advocates of Southern California and West Coast poetry as well as a nationally recognized poet, just sent me the book’s back cover material, which I reprint with her permission.

CAROL ELLIS — LOST AND LOCAL

“Leaving the theater I stand outside in a dark of black lipstick the world wears when everyone leaves.”

Language like this–savory, sensuous, and ripe with the unexpected–is among Carol Ellis’ strengths, along with an intelligence that converts the ordinary into the wild and strange. They pour from her, these poems, not in the form of stories, narrative, but in a profusion of responses to the world, the seen, the experienced and the imagined.

“Thunder. The dogs bark. The gods are angry say those who believe in gods. The gods are always angry or out in the back alley by the dumpster smoking cigarettes.”

Reader, think of Carol Ellis’ poems this way: it’s like stepping into the realm of dreams, but dreams wittier and more sumptuous than those that favor most of us each night.

*. *. *. *. * *

Carol Ellis’ Lost and Local possesses a lyrical acuity that is absolving and redemptive. She sees experience as a channel to catharsis. In poem after poem there’s a memorable humanity, a capacious, intelligent concentration immersed in the essential qualities of daily living. How rare it is to read a poet so exceedingly self-aware. These poems record those moments when we catch a glimpse of a world from which all the usual epithets have been stripped away. – David Biespiel

“Glowing with fervent sagacity, Carol Ellis’s LOST AND LOCAL reclaims the buoyant continuity of daily life as one of the prime affirmations enshrined in poignant poetic endeavors. The graceful rhythms of her prose poems, in particular, quietly extract a knowledge of the local’s meridians as all that seeks solace in our memories and encounters. LOST AND LOCAL is the rare book in which the cartography of the poems will inspire readers to find enough seclusion to read out loud to themselves, for what better way is there to absorb the amplitude of Ellis’s recitation — as intimate as it is shy, and eager to impart its watchwords.” — Bill Mohr

FROM MY BLOG, OVER THREE YEARS AGO:

Thursday, September 15, 2016: I WANT A JOB – Carol Ellis (Finishing Line Press, 2014)

“Post-Flaneur Poet”: “I Want a Job” by Carol Ellis

Back when I was just getting this blog underway, in the late spring of 2013, I wrote a brief comment on Oriana Ivy’s prize-winning chapbook, April Snow (Thursday, June 20). Finishing Line Press did a very handsome job on the printing of Ms. Ivy’s collection, and I have over a half-dozen other chapbooks from the same press with production values at least within the same range as April Snow. One has to wonder what happened to their sense of pride in the dismal job done on Carol Ellis’s very fine collection, I WANT A JOB. The printing looks no better than photocopying done on a machine that is running low on toner, and the small type only increases the text’s smudgy quality. Ellis deserved a far more substantial effort put into the publication of her writing.

Ellis, who now lives in Portland, Oregon, was born in Detroit and educated at the University of Iowa. After getting a Ph.D., with a dissertation on James Wright, she has (in her own words) “been around the academic block.” In punching the adjunct second-hand clock, with all of its constrictions on one’s own time to write, she somehow has enabled her imagination to sustain itself; the variety of tones in the poems and prose poems in her first book suggests that this collection barely serves as a representative presentation of that self-determination.

Chapbooks tend to be fallible collections; they all too often present a false sense of familiarity with the featured poet. In Ellis’s collection, one has a sense of three or four poems missing between each individual selection. I have never read a full-length manuscript by Ellis, so I confess that this is sheer guesswork, but rarely have encountered a first chapbook of poems that hinted at a substantial reservoir of other work awaiting revelation. As for the form of that undisclosed work, it is an equal guess as to how much of it might be prose poetry. Of the 25 poems in I WANT A JOB, 15 are prose poems, but Ellis is at ease in both arrangements, so the 60-40 proportion remains at the level of conjectural contingency. One could argue that the collection opens and closes with a prose poem; that simply reflects mathematical odds.

The poems in the second half of I WANT A JOB are especially noteworthy, and one in particular glows like a lyric translated from some obscure language into yet another language, before finding its unexpectedly perfected by this manumission from a long meditation. “First It Was Hot and Then It Was Dark” is not at all a typical poem, and part of its aura of tender supplication derives from the candid depiction of existential solitude in many of the accompanying poems. “Hot/Dark,” however, can more than stand on its own merits; it shimmers with tones of both restraint and an overflowing suffusion of the completely incomplete.

All this time trying hard to be alive,

the earth famously gone. Nothing to think

because one was thinking.

First it was hot and then it was dark.

She took off her sweater, turned on a light,

thought past the point of thinking.

Was there ever such a world repeated,

the entire place entirely too interesting

and entirely too forgotten?

This is one of those occasions in reading a collection of poems where one can do little else but put the book down, walk away, and challenge oneself to answer that question. A good place to begin would be to work on translating it into another language, for surely such a distillation of human consciousness can only be fully apprehended if reflected in the mirror of another concise diction and syntax.

Most likely, in fact, readers will find themselves putting this book aside after reading two or three pieces and giving themselves a chance to absorb sudden little bursts of sideways illumination. Ellis’s poetry is different enough from the fashion show of American poetry that it will take several readings to begin absorbing its whispered defiance of a lifetime of erasure. Ellis quotes James Tate’s poem, “Consumed”: “you are the stranger who gets stranger by the hour” in a poem entitled “Leaving Portland.” Ellis savors this transmogrification as a chance to help the reader apprehend the undercurrents of daily life, of how the visits to a plant nursery (“Getting Around Women”) or library (“The Book of Dad”) or bookstore (“Divinia Comedia”) or farmer’s market (“Repetition”) contain the rebuke of forestalled epiphanies. Her strategy is not that of a flaneur, however, for she is only too aware of how others thoughtlessly diminish one’s efforts to nourish the compassion of simple dignity (“Whore, Driving”).

In not flinching when confronted with this depleting pattern, this poet exhibits more courage than she will ever be given credit for. She’s not the only one, of course, of whom this can be said, but she is one of the few poets who understands the full measure of the imbalance.

“my future appears in leaves – the goodbye that does not think – the end of thinking – so I try to think more now – in the short space remaining – in the space allowed – but rather think about the sun and how right now it has the frightening power of a god – never underestimate a god – pray for mercy – gather nerve as one gathers flowers – the chuckling frogs – tucked into steep sides and the hard ache of a tall bird coming to find them.”

(”Frog Chuckle”)

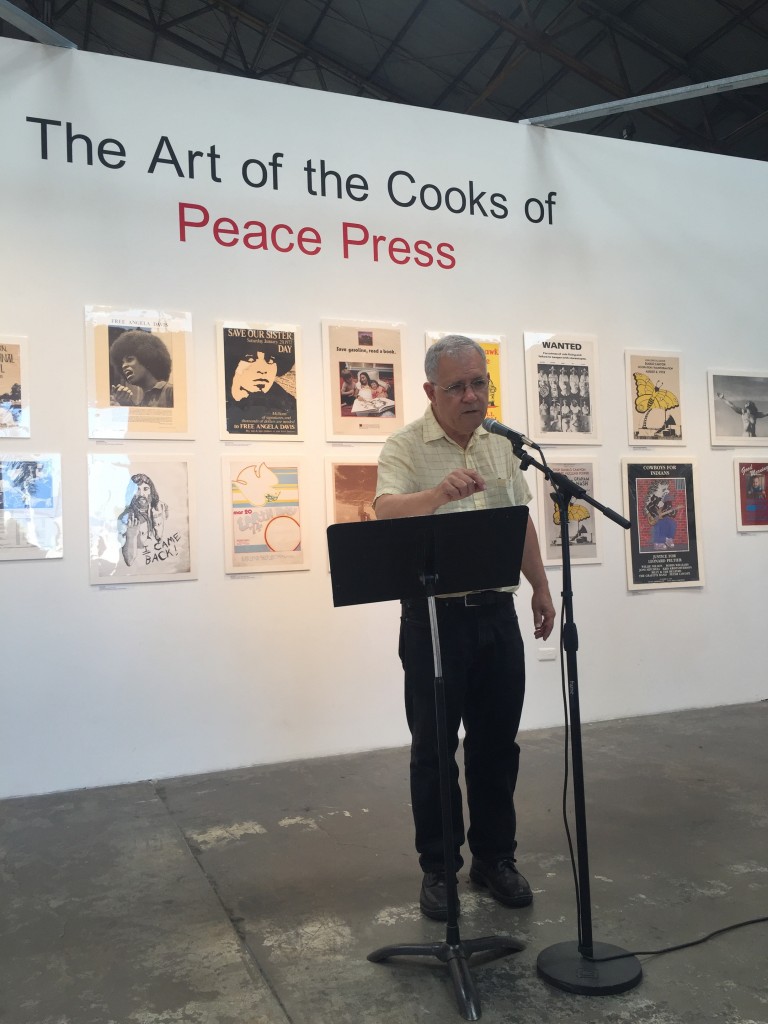

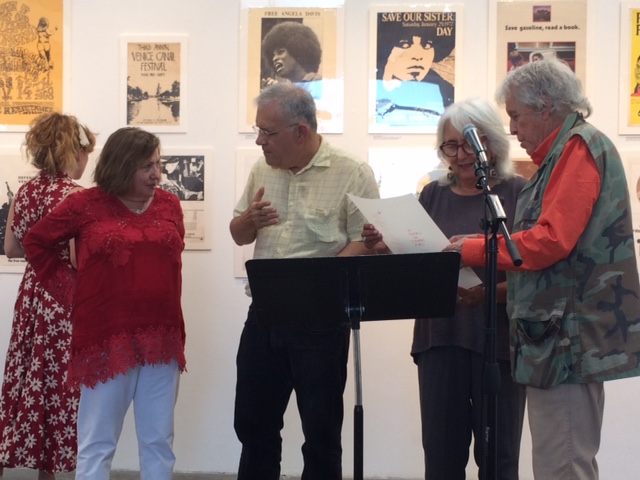

About Bill Mohr

About Bill Mohr